Courage, Cowardice, China, and Cushing

/by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

On June 17, 1843, Caleb Cushing went to dinner at Faneuil Hall. It had been a bruising year, and Cushing had barely managed to snatch victory from the jaws of humiliating defeat.

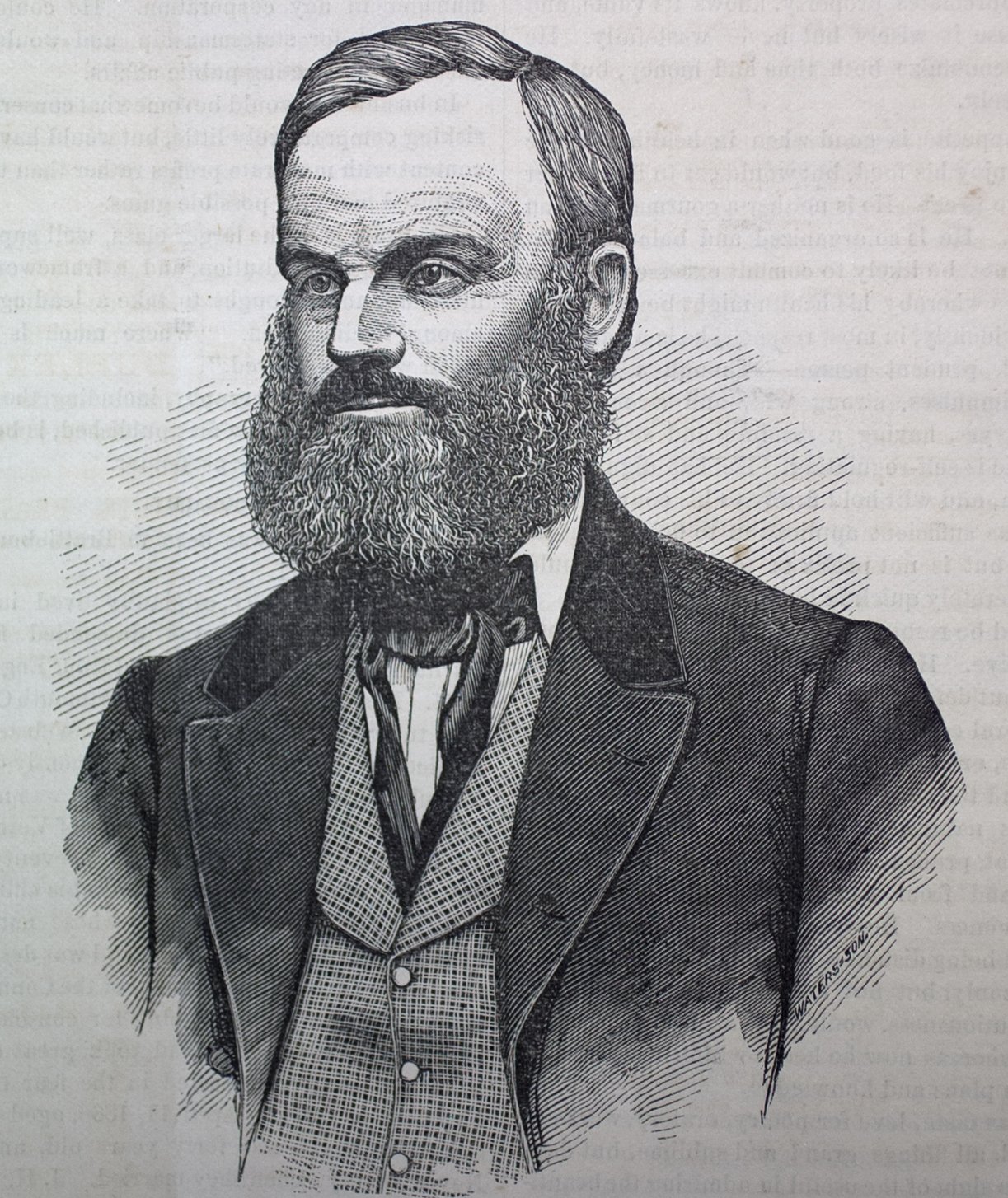

Cushing, then a Congressman from Massachusetts, was becoming known for his inconsistency and willingness to vote both for and against bills and change political parties as he saw an advantage. He had been nominated by President John Tyler to serve as Secretary of the Treasury, but the Senate refused to confirm him. He was nominated three times in one day, and as many times rejected. President Tyler, whose long relationship with Cushing deserves more than a passing line here, then appointed his friend to lead a delegation to China to secure a trade treaty. It was an opportunity for Cushing to rebuild his reputation, and he took full advantage of the months between his appointment and his departure to talk up the importance of his mission. Hence the dinner at Faneuil Hall, at which both President Tyler and Daniel Webster were also guests.

The occasion was the dedication of the Bunker Hill Monument, memorializing the battle where Cushing's fellow Newburyporter, Samuel Gerrish, had ignominiously contributed to the American defeat.

This seems to be a theme in my life and work, dear reader. Begin the week thinking about Caleb Cushing and the China Trade as we plan the China Trade Conference on October 28 (you should come, of course - click here for more), and then take what seems to be a completely left turn to write about Samuel Gerrish. Then, oh serendipity, find Cushing doing what you could not have imagined could be done - linking, as only a career politician could - the Battle of Bunker Hill and trade with China. I'll let Cushing take it from here...

Not merely relating to the conflict of 1775; not to the ever-remembered victory which ushered in our national existence ; nor to the scene which was the glorious dawn of our existence ; nor to the mere military triumphs, glorious as they were in that battle-day which is first among our annals of the war. I...see now, that peace has her triumphs, no less than more brilliant war...

I have myself been honored with a commission of peace, and am entrusted with the duty of bringing nearer together, if possible, the civilization of the old and new worlds - the Asiatic, European and American continents.

For though, of old, it was from the East that civilization and learning dawned upon the civilized world, yet now the refluent tide of letters - knowledge, was rolled back from the West to the East, and we have become the teachers of our teachers."

Cushing then turned dramatically to President Tyler, addressing him directly. "I go to China, sir, if I may so express myself, in behalf of civilization, and that, if possible, the doors of three hundred millions of Asiatic laborers may be opened to America. And if there is to be there another Bunker Hill monument, may it not be to commemorate the triumph of power over people, but the accumulating glory of peaceful arts, and civilized life."

Cushing's vision of China as an ancient center of learning, now fallen so far behind the United States that "we have become the teachers of our teachers", is patronizing at best. There are many other elements of Cushing's vision of his mission "on behalf of civilization" that are deeply problematic. Closer to the truth was his telling line about the "three hundred million" who would be "opened to America". Whatever else Cushing sought to achieve, his mission was clear. Through threat and flattery, coercion and conviction, he was to secure for the United States a treaty that would open up Chinese markets to American goods and vice versa. If he were to fail, England would have a critical advantage over the United States in international trade.

If the subsequent journey to China and the 1844 Treaty of Wanghia interest you, come to the conference, where Eric Jay Dolin and Dane Morrison will describe its impact far more eloquently than I ever could.

When America First Met China by Eric Jay Dolin, is an excellent overview of the early years of the China Trade. Dolin is a featured speaker at the Newburyport and the China Trade Conference on October 28.

Memory and meaning are my obsession. The Battle of Bunker Hill was, to Cushing, and many others, "the glorious dawn of our existence" as a nation, and there is some truth to that. Though the Provincial troops were defeated that day, they inflicted horrific casualties on the British troops, killing or wounding some thousand of them, out of a force of 2400. It was a watershed event, worthy of remembrance. Cushing employed the memory of Bunker Hill to argue that peace, and, self-servingly, diplomacy and trade were the new path to American victory. His speech was widely quoted in the publications of peace leagues across the country. It is worth mentioning, however, that Cushing arrived in China in February 1844 in a convoy of warships.

1848 View of Bunker Hill Monument, Charlestown, built 1824-43, Solomon Willard architect. Digital Commonwealth

Any historical event is unknowable, in a way. It is experienced differently by every person, whose perspective, experience, bias, and status influence what meaning they make of it. Facts can be secured, carved in stone, but meaning is endlessly shifting. Samuel Gerrish hiding behind a haystack, the blood and chaos and smoke of the fight before him, may be a coward, or a realist, or he may have been suffering the traumatic effects of decades of bloody military service. Several later writers argued that he had been a scapegoat for widespread failures of leadership at the battle. Caleb Cushing was certainly not representing his experience as he prepared to sail for China.

It is easy to distill a whole life to one line. The title of the earlier piece does just that. "Cowardly Colonel of Bunker Hill" is not the sum of Samuel Gerrish's life, though there is ample evidence that this is an accurate description of his observed behavior. Nor is Caleb Cushing's celebrated negotiation of the Treaty of Wanghia in 1844 an accurate summation of the life and work of a very complex man whose failure to speak and work against slavery may have been typical of his time, but still stands out as a failure of conviction. Today I am mulling over the meaning of courage, how it shifts in one's life, how I have been courageous or cowardly, and at times both simultaneously. It is part of the human condition to look for inspiration in the past. I think we can learn as much from moments when our courage fails.