Samuel Thomson was born in 1769 in Alstead, New Hampshire, which he described as a “wilderness”. At a young age, he became interested in the plants that grew near his farm, and apprenticed, informally, with a local healer, a woman well versed in herbal remedies. His biggest discovery, however, was made by accident when he sampled some wild lobelia inflata, known as Indian tobacco, which caused sudden and enthusiastic vomiting. At first, he thought it would be fun to trick other children into sampling his discovery and enjoying an afternoon of thunderous chundering (there’s always that one kid…). Later, after he had miraculously cured an ankle injury, his wife’s childbed fever, and other illnesses with steam and the liberal application of herbs designed to open “pathways of elimination”, he began to practice his unorthodox methods in Surry, New Hampshire and the surrounding area. Things did not get off to a promising start, and in 1809, Thomson was accused of murder, when one of his patients, Ezra Lovett, died after ingesting quantities of lobelia. He was acquitted, and the notoriety of the case, and Thomson’s strident defense of his methods against the attacks of the medical establishment, made him a celebrity.

Thomson was a man with the right message at the right time. His system of healing, accessible to all, fit in perfectly with Jacksonian ideals of individuality and populism, and extolled the virtues of folk wisdom and intuition over formal education. Thomson attacked the medical establishment in populist terms. “From those who measure a man's understanding and ability to be beneficial to his fellow men only from the acquisition he has made in literature from books…I expect not encouragement but opposition.” He boasted that anyone could follow his methods “without knowing a single letter of the alphabet.”

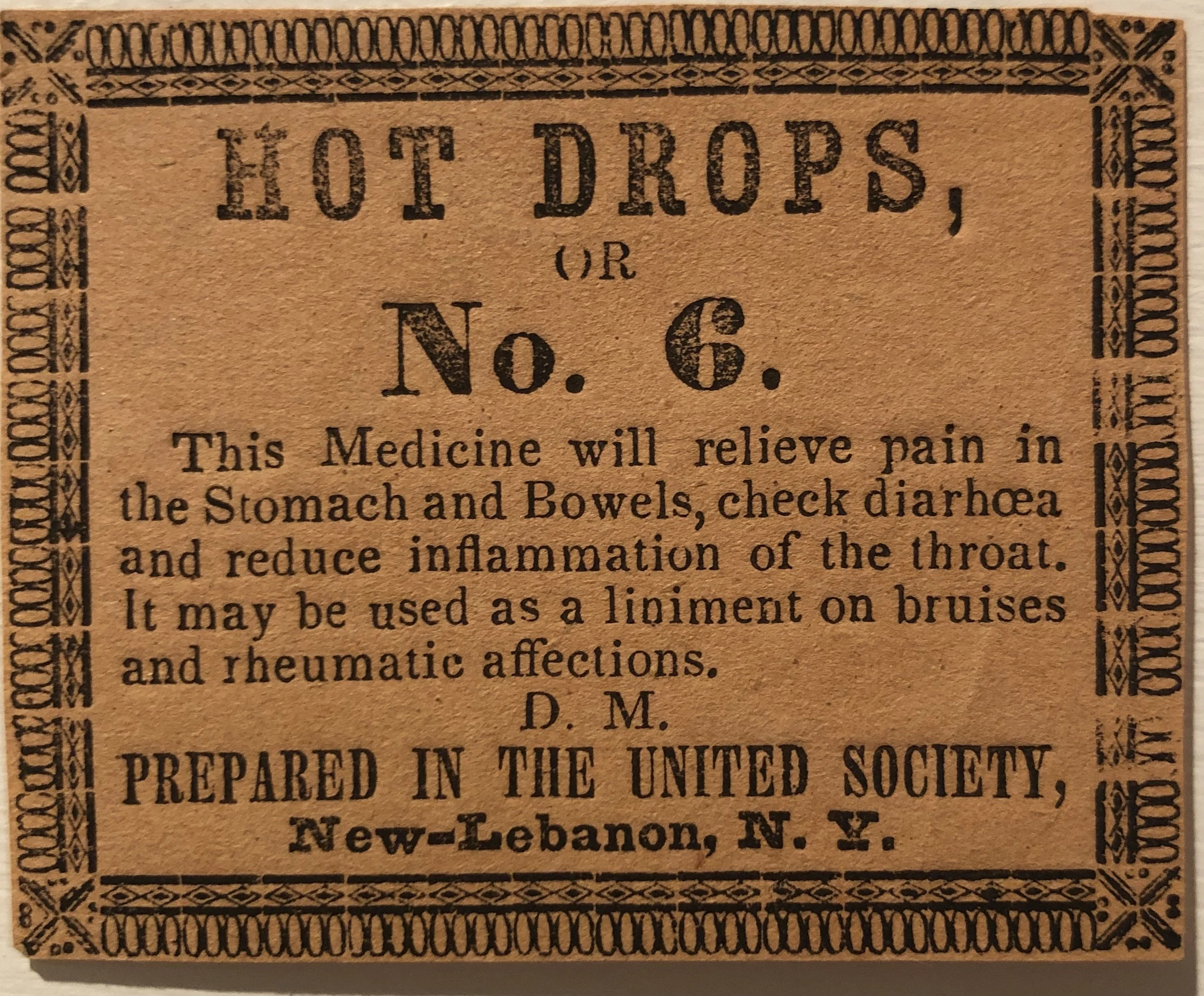

And he understood that his business would depend on direct sales. Thomson would advertise a free public lecture when he arrived in town, give a rousing speech excoriating the poisonous methods employed by the medical establishment, demonstrate his process, which was all about eliminating toxins through steam, purgatives and laxatives, and then offer to sell the right to become a “Thomsonian” practitioner, for a cost. He encouraged the practitioners to network with each other, recruit new agents for the cause, and so on. As his popularity grew, so did opposition from the medical establishment. Newspapers were quick to publish allegations that Thomsonian practitioners were steaming and poisoning their patients to death, and physicians and medical schools took out advertisements in the Newburyport Herald calling on their patients to resist “quackery” and eschew the “puke of lobelia”. After all, they mused, Thomson’s herbal remedies had long advertised their explosive effects with names like “screw augur! ram-cat! hell-scraper! and belly-my-grizzle”.

It was too late. After the publication, in 1822, of Thomson’s New Guide to Health, or Botanic Family Physician, Thomsonian establishments, known colloquially as agents of “family medicine”, in this case meaning it could be dispensed and applied at home, sprang up across the country. In Newburyport, in 1835, Dr. Dow announced that he had “taken that elegant and well-known place called Mount Rural, situated on High Street, Newburyport, and opened it as a Thomsonian Infirmary, for the sick and lame. This house is large and commodious, and for purity and salubrity of air, and beauty and extent of prospect of the surrounding country and coast, is not surpassed by any spot in New England.” He went on to reassure potential patients that “I here pledge on my honor that not one person ever died in my Infirmary,” despite the rumors. After a certain period of gut-wrenching unpleasantness, patients could expect his treatment to “penetrate the system, equalize excitement, remove obstructions, cleanse the stomach and bowels, purify the blood, remove disease from lungs and liver,” and eradicate a host of issues, from depression to infertility and cancer.

Thomson died in 1843, and though herbalism and so-called botanic cures continued to flourish, his particular methods and grassroots marketing structure began to fade. Herbalism became increasingly part of a professionalized school of practice.

When James and I were dating lo these many moons ago, I had the sniffles, and he told me that he would make me up an old family cure – whiskey, garlic, ginger, cayenne pepper, honey, lemon, and habanero sauce mixed with hot water. He made it. I, always a sucker for anything with a family story behind it (and a sucker for James himself, of course), struggled through it. After a certain amount of gasping and sweating, I questioned its origins. “Oh, I’m sure it’s SOMEONE’s old family cure, but certainly not mine,” he laughed, as my face went a blistering red. I was enraged. “Got rid of the sniffles though, didn’t it?” Fair enough. Reader, I married him. After all, it’s nice to have a (Thomsonian) doctor in the family.