A Stitch in time

/a blog by Bethany Groff Dorau

This morning, a package arrived at the Museum of Old Newbury.

It was not a ball.

This, you see, is a joke in my house. Whenever a package arrives that is flat or rectangular, or clearly a jewelry box, my dad earnestly declares, “I think it’s a ball”. It was a busy morning at the Museum of Old Newbury, and our newest intern, Lilly, had been stuck with a series of rather dull tasks. To make it up to her, Lilly was given the pleasure of opening this package. She undertook the challenge with characteristic efficiency. She worked quietly, an occasional small "hmm" to remind us that she was still working on it. She removed tape, bubble wrap, and a moving blanket. When she was done, she stood up without saying a word and looked at me, wide-eyed, holding a large framed sampler, stitched in 1811, by a girl named Eunice G. Sawyer.

Eunice G. Sawyer sampler, 1811. Photograph by Bob Watts.

I have a complicated relationship with samplers. I grew up in a bit of a crafty household, and we were all expected to learn how to sew and crochet and knit. My talents lie in other areas, and I hated sitting still. I was, I suppose, what once was called a tomboy. I thought draft horses and battle plans and books about locomotives and drilling rigs and aircraft carriers were amazing and that was enough to set me outside the ribboned (and later, lip-glossed) throng of girlhood.

The author, age 10. While my sister was learning to embroider, I much preferred the company of draft horses and goats.

And so, samplers to me smack of a certain kind of oppression. What if, like me, the girl in question wanted nothing more than to be driving a wagon or threshing grain or climbing a tree? What pleasure would there have been in painstakingly stitching a row of letters to be hung in the parlor and framed - an advertisement that this girl would be a patient, cultured, literate wife?

Of course, what I overlook is that nobody is exactly like me. This is the beauty of humanity, and, for historians, the sorrow. How can we know, unless she tells us, how Eunice Greenleaf Sawyer, age nine, felt about hours of stitching on her sampler? She may have loved the feel of the silk thread slipping through her fingers - the colors, now faded, that she wove into her masterpiece. She (though she is my fourth cousin), is, and will remain, a mystery to me, until such time as we find that cache of letters where she expounds upon her ecstasy (or agony) at the prospect of working the needle.

The story of this sampler, and the girl who worked it, will be told as we uncover it. With a certain amount of envy, I have handed over the lion’s share of the research on this piece to our very capable, very thorough Williams College intern, Annabelle, who dived right in. If Eunice Greenleaf Sawyer is to be found, Annabelle will find her.

I am not a sampler expert. I have already confessed my instinctive aversion to girlhood arts as a broad category. But any one sampler is a document, and though patterns and schools governed certain elements of sampler creation, there were always choices made in the selection of subject and text. Eunice, who turned nine years old in 1811, chose a rather somber poem about grief, depression, and comfort, and the last line reveals that the poem is an admonition to herself. In particular, it is a wish to be a balm to the wounds of others. A noble sentiment, and one that seems appropriate to the recently bereaved.

In 1811, Eunice Greenleaf Sawyer’s father had been dead for two years, and a brother had died the year before she was born. There was not, as far as can be easily ascertained from the record, a close recent bereavement, though death was closer at hand in the early 19th century than it is today. I wondered if this was a mourning piece.

The voice in my head, the same one that repeats “It’s a BALL!” in my dad’s voice, also repeats “The simplest answer is often the right one,” in my great-aunt Emily’s voice. Oh, how I miss her.

In 1811, when these threads were worked, joyfully or otherwise, Newbury had a new (as of 1808) meetinghouse in the Belleville neighborhood, officially the fourth parish of Newbury, stretching from the northwest side of Oakland Street to the Artichoke River. Though we do not know (yet) exactly where she lived, Eunice Sawyer had relatives all over Belleville.

The Belleville section of Newbury, c.1851 – North Street is now Oakland Street.

The poem that she carefully stitched was pulled from a didactic text, an English book of romantic sensibilities authored by a Miss Charlotte Palmer and published in 1780. It’s title? Female Stability; or the history of Miss Belville. Coincidence? Perhaps, but Aunt Emily would have told you that there is no such thing.

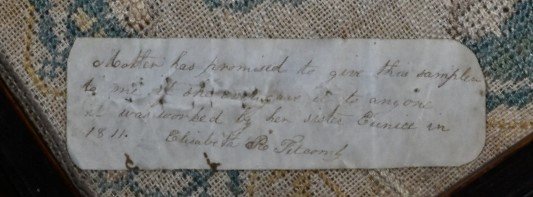

Although I am not drawn to samplers, I do love a darkly romantic poem, rendered extra gloomy by rows of “x”s. But the element of the piece that caught my eye, and stole my heart, is a piece of paper affixed to the lower left corner. It says, “Mother has promised to give this sampler to me. If she ever gave it to anyone. It was worked by her sister Eunice in 1811”. It is signed “Elisabeth R. Titcomb”.

The historian in me loves this note because, in a world where there were multiple Eunice G. Sawyers alive in 1811, we can determine conclusively that this was our Belleville gal. But it’s more than that. It captures a chain of memory, a sister’s affection, and a little possessiveness from a third born child who wanted to make sure her siblings knew that this piece was claimed.

Eunice died just after her 20th birthday, of tuberculosis. She was staying in Boston with an uncle who had taken on a paternal role after her father’s death, and she is buried there. Her sister Hannah, the “mother” in the note, lived for another fifty years. Elisabeth R. Titcomb, her niece, died in Chicago in 1917, and somehow this treasure wound up in a thrift shop back in New England. According to the letter from the donor, it was purchased around fifty years ago and made its way to Nevada, to be packaged back up and sent to us.

The owner of this sampler, perhaps aided by the note identifying it as a precious family piece, knew that it needed to be with people who know her family. We know the Sawyers and the Emerys and the Greenleafs. We can connect Eunice to her neighbors. We know that she was named after her aunt, and that her brother died in France, and that her grandmother left Eunice some shares in the Newburyport Turnpike. And so, while we will likely never know how she felt about her needlework, this gift is a gateway into her too-short life, her sister’s love, and the ceaseless pull toward home.