Silverware, Sex, and Stirpicults: John Humphrey Noyes and Oneida Community Silver

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

Part Three This is a continuation of a previous article. For the last installment, click here.

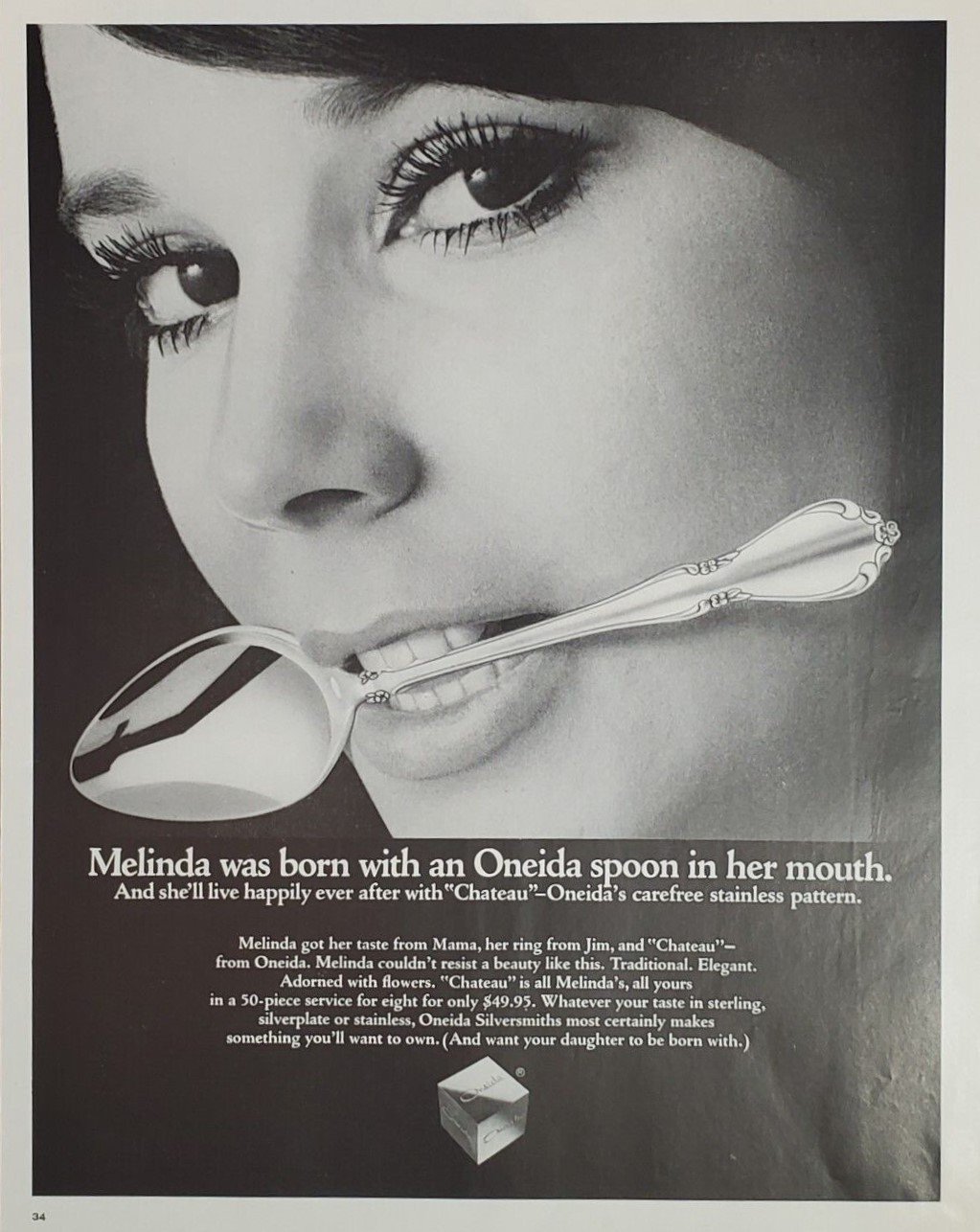

Don't you worry, my friends. This is the last naughty spoon ad to which I will subject you. But still, it does get the point across, does it not? Over fifty years later, it still gets a "whoa!" from my very worldly officemate.

The overt sexiness of Oneida in the 1960's is a not-so-subtle nod to the Oneida Community of a century earlier, a bastion of "complex marriage" where all community members were considered equally married to each other, their sexual "interviews" charging the spiritual batteries of the community in which they lived, worked, and played.

When we left our dubious hero John Humphrey Noyes, founder of the Oneida Community, whose family hailed from Newbury, and whose exploits were breathlessly reported in the sizzling pages of the Newburyport Herald, he had fled from the law for the second time in his life. First, in 1848, he had hightailed it from Putney, Vermont, to establish the community in Oneida, New York which, by almost any measure, had been a roaring success. Then, thirty years later, amid internal upheaval and national debate over the Mormon practice of polygamous marriage, and believing he was about to be charged with statutory rape, Noyes left New York for Niagara Falls, Canada, never to return.

Two months after his exit, Noyes sent word to his followers that it was time to end the practice of complex marriage, the foundational principal of the Oneida community. At 10 a.m. on August 28, 1879, the doors closed on the last "interview." It should have been the end of it all, and in a way, it was. But it was also the beginning.

John Humphrey Noyes (1811-1886), leader of the Oneida Community, shortly before his flight to Canada.

The Community was in turmoil. Noyes' attempts to install his son Theodore as his successor had backfired after the younger Noyes turned out to be less devout and more monogamous than his father had realized. The industrial endeavors at the heart of the Community were increasingly complex and the Community was nearing bankruptcy. And so, in 1881, the group abandoned communal ownership, the other foundational principal of the group, and formed a joint-stock company. Members of the Community were given stock in this new company, Oneida Community Limited. Older members received support payments, and Noyes himself was provided with a house in Canada, a horse and carriage, and a stipend for life. John Humphrey Noyes lived for seven more years, dying on April 13, 1886. His body was returned to his beloved Oneida and buried there with other members of the Community.

And then what? I will admit that my heart goes out to the children of Oneida, those who had been raised to believe in the possibility of sinless perfection and a benevolent, sustaining community that would provide for them. And this is where my own experience of the end of communal life intrudes on this tale.

I was raised on a commune too, except we had no successful industry, no free love, and no mansion houses. My parents were followers of a charismatic preacher named Sam Fife, and, guess what? He was all about sinless perfection. Unlike John Humphrey Noyes, however, Sam Fife preached that the chosen people had to survive the end-times and the best way to do that was to decamp to the wilderness of northern Canada. So, I suppose we have that in common with Noyes as well. We all ended up in Canada, though I think he may have had the better deal.

Let's just say that I understand deeply and personally how difficult it is to transition to society at large when you have been raised apart. For the Oneidans, there was the sometimes desperate scramble for a spouse as the Community disintegrated. And there was the question of whose children were whose, since in some cases only the mother was known conclusively. And if men had fathered multiple children, there was the question of which mother to marry and which adult children could marry each other. In the game of marital chairs of the early 1880's, some lost out and experienced isolation and profound loneliness for the first time.

The managers of Oneida Community Limited did their best to parcel out the assets of the Community, building houses on formerly shared land and trying to provide some measure of financial and social stability, but the business, controlled by older members of the former community, was floundering.

John Humphrey Noyes was at it again, this time from beyond the grave. So attached were his former followers to the advice of their charismatic leader that the board members of Oneida would have seances to seek financial advice from Noyes who, perhaps unsurprisingly, generally came back from the dead to agree with whoever was asking.

Finally, in 1893, one of the "stirpicults," children born as part of the Oneida Community's genetic engineering project that began in 1869, put an end to the seances and wrested control, finally, from the cold dead hands of his father. Twenty-five year old Pierrepont Noyes replaced the elderly board, hired his half-brothers and sisters to help run the company, and at twenty-nine, became General Manager of the Oneida Corporation.

It was Pierrepont who decided that the company should sell off the animal traps business and focus on silverware. A new factory was built in 1913, and the company was reorganized to honor many of the principals that were the best of the Oneida Community. Decisions were made by consensus, intellectual pursuits, recreation, and leisure time were valued, and profits, which soared, were often put to community purposes. Still, the sexual exploits and fringe beliefs of their parents and grandparents was increasingly embarrassing, and a liability to the thriving international corporation, and in 1947, much to this historian's dismay, the documents and records of the Oneida Community and John Humphrey Noyes were taken to the dump and burned by their descendants.

By 1956, re-branding was in full swing, with a full-page advertisement in the Ladies Home Journal touting the company's "small beginnings in agriculture" and their principals of "hard work, meticulous craftsmanship, and never underestimating the value of a woman." And the clean-cut 1950's young executive looking back from the page? John Humphrey Noyes' grandson, P.T. Noyes, who controlled the company until 1981. No mention of communism, unsurprisingly.

Still, if the descendants of John Humphrey Noyes knew anything, it was the power of sex and industry, the twin pillars of the original Oneida Community, and by the late 1960's, a time when, once again, America was examining its feelings about monogamy, work, and spirituality, Oneida silverware was sold in the mouths of beautiful young women. John Humphrey Noyes must have been smiling.