Hidden History: Newburyport's Swedish Connection

(originally published published June 10, 2022)

...a blog by Bethany Groff Dorau

My grandfather was born in Boston in 1909, the firstborn son of Irish parents (with a long stayover in Maritime Canada). When he was five years old, his father died, leaving his mother with four children. If you did that math, my grandfather was five years old and the ELDEST of four. Unable to support her young family, his mother put her children in a Catholic orphanage and then took them back, one at a time, starting with the youngest.

This is my grandfather’s story, and it is (mostly) true. What is certainly true is that after a brutal childhood – he was left-handed and was particularly targeted for this “sin” - he was sent off to work on a South Shore farm and became Swedish.

This is a story for another time, but let me just say that having determined that the life of a Swede was preferable to the life of a semi-orphaned Irish lad, my grandfather stole the identity of a recently deceased Swedish boy, and 13-year-old John Muzrall became 16-year-old John Erickson and ran away to New York City and hopped a ship. He spoke Swedish, lived with a Swedish family, the Dahlgrens, in Brooklyn, and was even elected as a spokesperson for a Swedish labor union. For four years, my grandfather was Swedish.

John Muzrall’s application for certification of identity in 1927, approved in 1929.

John Erickson was finally laid to rest when John Muzrall was 17 and shipped out on the Leviathan under his true name and age as a “messman”, but for the rest of his life he thought of himself as a bit more Swedish than Irish. My grandfather died at 91, here in Newburyport. In his final days, he slipped in and out of consciousness, speaking only Swedish.

Such is the shifting nature of identity.

When Swedish artist Tina Rawson, a friend from years ago, stopped by the Museum of Old Newbury several months ago to check out my new(ish) digs, I thought of my grandfather, the fake Swede. At one point in the conversation, she made a comment to the effect that, historically, she did not believe there was a significant Swedish population in Newburyport. Being the obstinate history nerd that I am, I set out to prove her wrong.

When I was writing my second book, A Newburyport Marine in World War I: The Life and Legacy of Eben Bradbury, I came upon a startling statistic. Almost one-third of WWI draft registrants in 1917-1918 in Newburyport were foreign-born. One third. This, to me, speaks to the ethnic diversity of our fair city, at least in the past, and so I was reasonably sure I would come across some Swedes.

As you may imagine, this being a port town, there were Swedish connections long before Swedish people begin to appear in Newburyport census records as permanent residents.

In 1850, Joanna Jackson, 49, is listed as the wife of Nathaniel Jackson, surveyor of the port. This is the first census in which Sweden appears as the country of origin for Newburyport residents in significant numbers. Along with Joanna, Francis C Stromberg plied his trade as a gilder, Charles Johnson as a painter, Augustus Hanson as an able seaman, Lewis Stanson, mariner, and more. With their families, they constituted about a dozen residents.

The Swedish population of Newburyport seems to have grown steadily until it numbered over 30 in 1900. Keep in mind that this number does NOT include the children of Swedish parents, and so the community was significantly larger. Deeper research will reveal a network of business, neighborhood, and family networks that will shed further light on how these people lived and worked in this community, but knowing that they were here, that they often came over as adults, and that their community seems to have shifted from maritime workers and fine artists to factory and domestic labor is also an interesting part of the story.

The 1910 census includes a “real” John Erickson and his family, employed in the comb factory and living on Bromfield court.

Whether you have a Swedish connection, true or invented, please join us on June 25 for Midsummer Magic: Creating Swedish Folk Art in the Garden. We hope to explore more of this community’s immensely rich history in the future, and creating art seems like an excellent way to start. I will be painting for my grandfather, and for his Brooklyn substitute mother, Naomi Dahlgren, who let him live as a Swede. She had secrets of her own…but that really is a story for another time.

Whether you're Swedish or not, you are welcome to make some art in our garden on June 25!

A Stitch in time

a blog by Bethany Groff Dorau

This morning, a package arrived at the Museum of Old Newbury.

It was not a ball.

This, you see, is a joke in my house. Whenever a package arrives that is flat or rectangular, or clearly a jewelry box, my dad earnestly declares, “I think it’s a ball”. It was a busy morning at the Museum of Old Newbury, and our newest intern, Lilly, had been stuck with a series of rather dull tasks. To make it up to her, Lilly was given the pleasure of opening this package. She undertook the challenge with characteristic efficiency. She worked quietly, an occasional small "hmm" to remind us that she was still working on it. She removed tape, bubble wrap, and a moving blanket. When she was done, she stood up without saying a word and looked at me, wide-eyed, holding a large framed sampler, stitched in 1811, by a girl named Eunice G. Sawyer.

Eunice G. Sawyer sampler, 1811. Photograph by Bob Watts.

I have a complicated relationship with samplers. I grew up in a bit of a crafty household, and we were all expected to learn how to sew and crochet and knit. My talents lie in other areas, and I hated sitting still. I was, I suppose, what once was called a tomboy. I thought draft horses and battle plans and books about locomotives and drilling rigs and aircraft carriers were amazing and that was enough to set me outside the ribboned (and later, lip-glossed) throng of girlhood.

The author, age 10. While my sister was learning to embroider, I much preferred the company of draft horses and goats.

And so, samplers to me smack of a certain kind of oppression. What if, like me, the girl in question wanted nothing more than to be driving a wagon or threshing grain or climbing a tree? What pleasure would there have been in painstakingly stitching a row of letters to be hung in the parlor and framed - an advertisement that this girl would be a patient, cultured, literate wife?

Of course, what I overlook is that nobody is exactly like me. This is the beauty of humanity, and, for historians, the sorrow. How can we know, unless she tells us, how Eunice Greenleaf Sawyer, age nine, felt about hours of stitching on her sampler? She may have loved the feel of the silk thread slipping through her fingers - the colors, now faded, that she wove into her masterpiece. She (though she is my fourth cousin), is, and will remain, a mystery to me, until such time as we find that cache of letters where she expounds upon her ecstasy (or agony) at the prospect of working the needle.

The story of this sampler, and the girl who worked it, will be told as we uncover it. With a certain amount of envy, I have handed over the lion’s share of the research on this piece to our very capable, very thorough Williams College intern, Annabelle, who dived right in. If Eunice Greenleaf Sawyer is to be found, Annabelle will find her.

I am not a sampler expert. I have already confessed my instinctive aversion to girlhood arts as a broad category. But any one sampler is a document, and though patterns and schools governed certain elements of sampler creation, there were always choices made in the selection of subject and text. Eunice, who turned nine years old in 1811, chose a rather somber poem about grief, depression, and comfort, and the last line reveals that the poem is an admonition to herself. In particular, it is a wish to be a balm to the wounds of others. A noble sentiment, and one that seems appropriate to the recently bereaved.

In 1811, Eunice Greenleaf Sawyer’s father had been dead for two years, and a brother had died the year before she was born. There was not, as far as can be easily ascertained from the record, a close recent bereavement, though death was closer at hand in the early 19th century than it is today. I wondered if this was a mourning piece.

The voice in my head, the same one that repeats “It’s a BALL!” in my dad’s voice, also repeats “The simplest answer is often the right one,” in my great-aunt Emily’s voice. Oh, how I miss her.

In 1811, when these threads were worked, joyfully or otherwise, Newbury had a new (as of 1808) meetinghouse in the Belleville neighborhood, officially the fourth parish of Newbury, stretching from the northwest side of Oakland Street to the Artichoke River. Though we do not know (yet) exactly where she lived, Eunice Sawyer had relatives all over Belleville.

The Belleville section of Newbury, c.1851 – North Street is now Oakland Street.

The poem that she carefully stitched was pulled from a didactic text, an English book of romantic sensibilities authored by a Miss Charlotte Palmer and published in 1780. It’s title? Female Stability; or the history of Miss Belville. Coincidence? Perhaps, but Aunt Emily would have told you that there is no such thing.

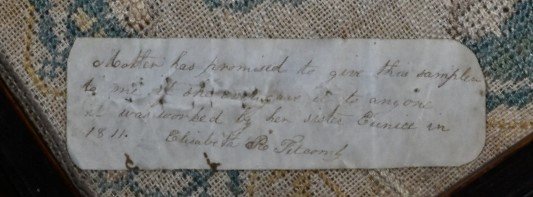

Although I am not drawn to samplers, I do love a darkly romantic poem, rendered extra gloomy by rows of “x”s. But the element of the piece that caught my eye, and stole my heart, is a piece of paper affixed to the lower left corner. It says, “Mother has promised to give this sampler to me. If she ever gave it to anyone. It was worked by her sister Eunice in 1811”. It is signed “Elisabeth R. Titcomb”.

The historian in me loves this note because, in a world where there were multiple Eunice G. Sawyers alive in 1811, we can determine conclusively that this was our Belleville gal. But it’s more than that. It captures a chain of memory, a sister’s affection, and a little possessiveness from a third born child who wanted to make sure her siblings knew that this piece was claimed.

Eunice died just after her 20th birthday, of tuberculosis. She was staying in Boston with an uncle who had taken on a paternal role after her father’s death, and she is buried there. Her sister Hannah, the “mother” in the note, lived for another fifty years. Elisabeth R. Titcomb, her niece, died in Chicago in 1917, and somehow this treasure wound up in a thrift shop back in New England. According to the letter from the donor, it was purchased around fifty years ago and made its way to Nevada, to be packaged back up and sent to us.

The owner of this sampler, perhaps aided by the note identifying it as a precious family piece, knew that it needed to be with people who know her family. We know the Sawyers and the Emerys and the Greenleafs. We can connect Eunice to her neighbors. We know that she was named after her aunt, and that her brother died in France, and that her grandmother left Eunice some shares in the Newburyport Turnpike. And so, while we will likely never know how she felt about her needlework, this gift is a gateway into her too-short life, her sister’s love, and the ceaseless pull toward home.

Where's Waldo? Why Newburyport, of course.

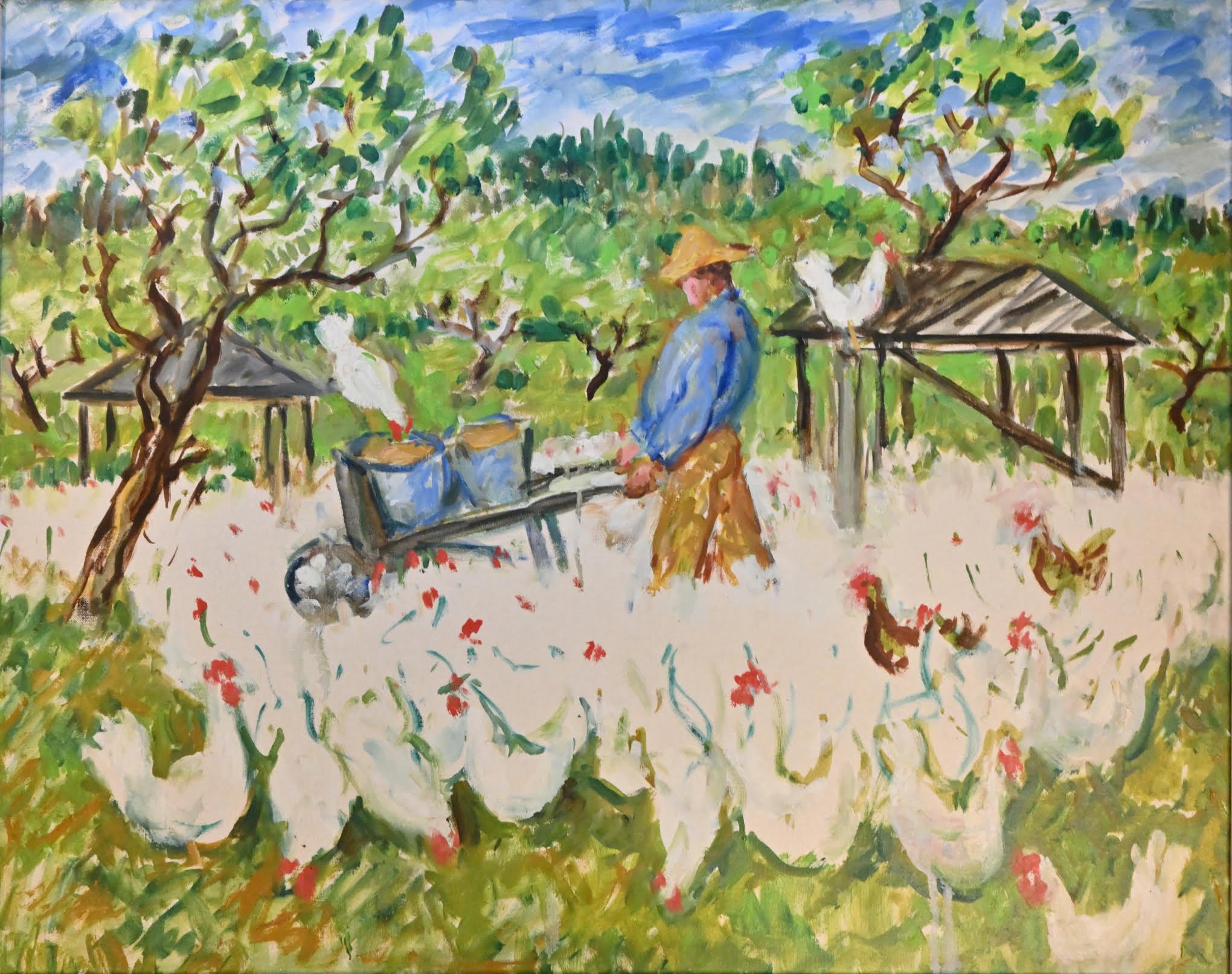

Painting by Waldo Peirce, gift to Paul Plourde, oil on canvas, 1969

a blog by Bethany Groff Dorau

I fall in love with dead people about a dozen times a day, by which I mean that some turn of phrase, some item on an inventory, some bit of a recollection or an object saved, a dusty bit of something is added to a keepsake box in my heart. It’s strange, but that’s how it feels – like love, like finding an essential bit of humanity and understanding something about what it means to be here right now, alive in this moment.

A few months ago, someone challenged my description of an ancestor as one of my “dead friends.” It is a bit of a disingenuous turn of phrase, of course, as a living friendship is mutual and ever-changing, but it feels true in that I think about many of these people the same way I think about my living friends. Who did they know? What would they think about the state of the world? How do their lives and passions connect with other friends of mine?

It will come as little surprise, then, that today I am in love with Waldo Peirce. He knows other friends of mine, living and dead, and memories of him are all around this community. He is a new friend, and I think the story of our meeting bears repeating.

Portrait of Waldo Peirce by George Bellows (1920), image courtesy de Young Museum

Several weeks ago, a woman contacted the museum to ask if we were interested in a painting by a local artist. We said yes, somewhat hesitantly, because “are you interested” often means “Would you be interested in buying?” Imagine our delight when this woman and her husband came to the museum with a large painting of a man with a flock of chickens, and reams of background information – letters, bills, exhibition catalogs, things they had found in the yard of their house, where Waldo Peirce once lived. They were moving out of state, they said. They loved this painting and they wanted it to stay in Newburyport. They had received the painting from the previous owner of the house, whose death from COVID rendered their gift even more poignant and meaningful.

And it was a gift. They understood its monetary value and chose to honor their few years in the community by giving the painting and its associated materials to the Museum of Old Newbury, and, by extension, to all of us. This, to me, is always a bit of a shock, accompanied by deep gratitude. In a world of people who grab and hoard, I am still in awe of the givers, who understand what it means to leave something important in trust to a community.

The painting is temporarily displayed in the office, and so when one of our board members came for an event, she stopped and laughed. “He worked on Inn Street before everything was torn down,” she said. “We used to try to sneak a peek and see if Mr. Peirce had any naked people in his studio.” And this is what happens to me in a moment like this. This board member, who I know well, is suddenly a girl with an ice cream cone, and Inn Street is a warren of artists, shops, and alleys, and Waldo Peirce is alive again and be-smocked, a dripping brush held in his mouth, as he considers whether to paint clothing on a reclining model, much to the delight of Newburyport’s roaming young folks.

Inn Street, c. 1960’s. The Plourde barber shop and Waldo Peirce’s studio are out of frame along the left side of the street.

Waldo Peirce, though related to Newbury’s early Peirce family, grew up in Maine. It is beyond my power to do justice to his remarkable life, so I will quote a 2018 article in the Portland Monthly magazine. “Rabelaisian, bawdy, witty, robust, wild, lusty, protean, lecherous, luscious, the kind of man Ernest Hemingway wished he could be, Waldo Peirce (1884-1970)…devoured life.” Waldo Peirce was a Harvard football player, a competitive swimmer, a voracious lover, and by all accounts, a devoted father and grandfather. But it was his personal courage, evidenced in his role as volunteer ambulance driver for the American Field Service that made him my friend. You see, I know them, the Harvard and Yale boys who thought the Great War would be a grand adventure. I know them, in part, because for 21 years I had a role in the management of Beauport, the home of Henry Davis Sleeper, who was one of the founders of the American Field Service with his friend and neighbor A. Piatt Andrew. Sleeper, Peirce, and Andrew were all awarded the Croix de Guerre for conspicuous bravery by the French government. Waldo Peirce’s portrait of A. Piatt Andrew, given to their mutual friend Isabella Stewart Gardner, is a striking memento to all involved in the service.

A Piatt Andrew by Waldo Peirce, c. 1918

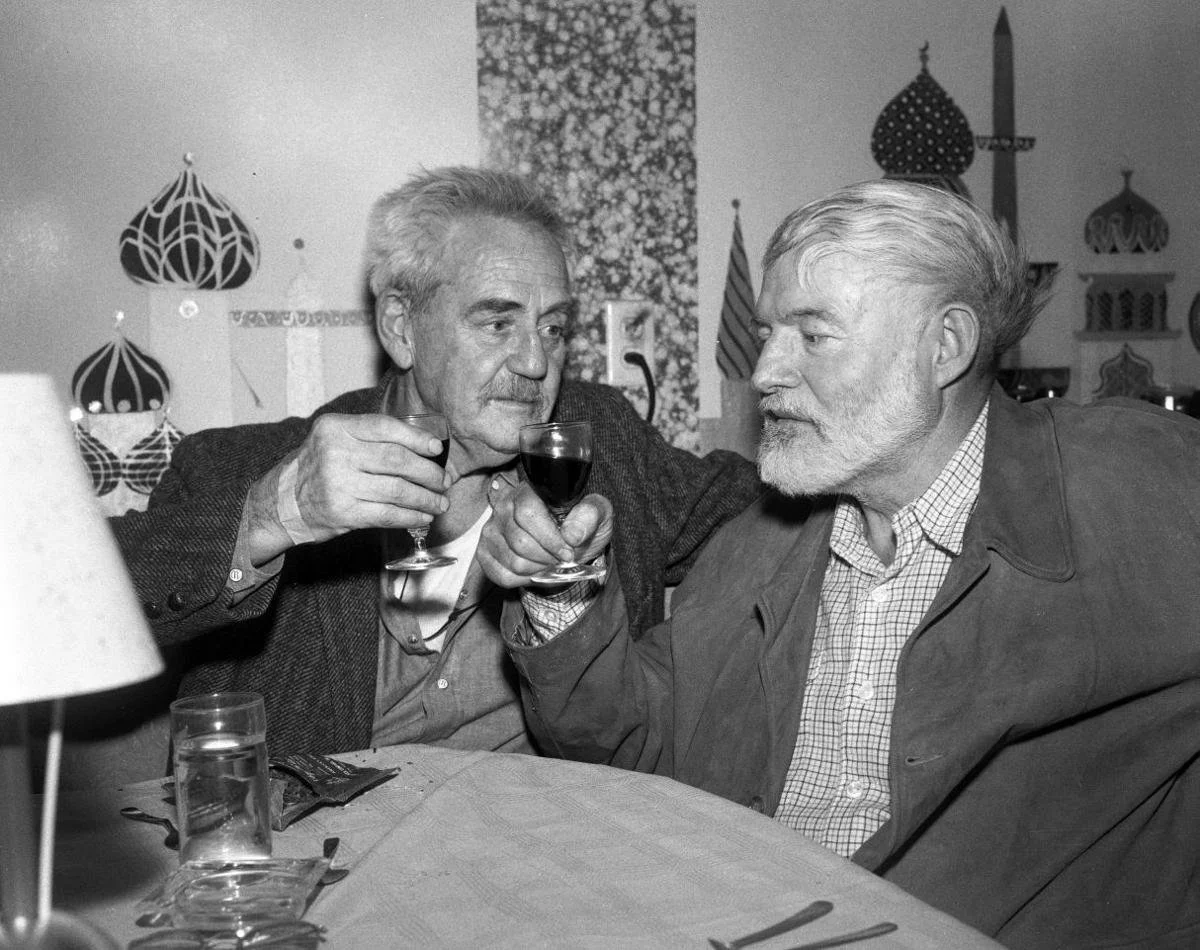

Of course, the most famous ambulance driver in World War I is Ernest Hemmingway, and it was the shared wartime experiences of these two men that forged an intimate friendship. In 1927, the pair ran with the bulls in Pamplona, and for the rest of their lives, both inspired the art of the other.

Peirce and Hemingway in 1959. Image courtesy Tucson Sun.

Waldo Peirce lived in Newburyport off and on for decades, and the first gift of this painting was made from the artist to Paul H. S. Plourde, Peirce’s barber, whose shop was near his studio on Inn Street. 53 years later, it walked through my door.

I think of how many times I have met someone and found myself using the shorthand “I’ve heard so much about you,” a way of saying, “I know you a bit already.” This is how I feel about Waldo Peirce. I know him a bit already. How could you not, with quotes like this? From his nephew, “I remember a musty tobacco smell coming from a huge, gentle, and confident man with an impressively grizzly beard. He had a deep, gruff and beautiful voice,” and from an old friend, Vincent Hartgen, “Waldo was a pretty good artist, but he was truly a great man.”

The Barber Shop, 1949, oil on canvas, by Waldo Peirce.

For me, the beard is key to his allure, as is the height – he was over 6 feet tall, but it was his writing, not his art, that I will tuck into the keepsake box in my heart. Here is his homage to his friend Richard Hall (1894-1915), published shortly after Hall’s death while driving an ambulance in France.

Gentlemen at home, you who tremble with concerns at overrun putts, who bristle at your partner's play at auction, who grow hoarse at football games, know that among you was one who played for greater goals--the lives of other men.

There in the small hours of Christmas morning, where mountain fought mountain, on that hard bitten pass under the pines of the Vosgian steeps, there fell a very modest and valiant gentleman.

-Friends of France, 1916

Waldo Peirce sketching on the side of an ambulance, circa 1915-1916. Courtesy of the Archives of the American Field Service and AFS Intercultural Programs (AFS Archives.)

Imagine my surprise, and then no surprise at all, when one of the artifacts from Waldo Peirce’s Newburyport home turned out to be a small piece of type with the name of Harold DeCourcy, a fellow ambulance driver in France. Did it fall from the pocket of his old friend when he came to visit Peirce decades later in Newburyport? Was it a memento of their time together? We will likely never know. What I do know, for certain, is that the gift of that painting ripples outward into my life, and that of the museum and the community. It is a powerful reminder of how much is yet to be learned, and how many dead friends we have yet to meet.

Found while metal detecting at the Waldo Peirce home. Harold DeCourcy was a fellow ambulance driver in WWI.

Do you have images and/or memories of Waldo Peirce? Please share them with the Museum, as it will enrich our understanding of this artist's time in Newburyport. Email info@newburyhistory.org.

Bloom Where You’re Planted

a blog by Bethany Groff Dorau

On April 7, 2020, I was alone in my house. We were all alone in our houses, except for those of us who were locked in with our family members. It was too early for “bubbles” and “pods”. I thought, perhaps we all thought, that this would all be over soon, and so, while I waited, I thought I would get to know my landscape a bit better. And since what is now my yard has been my family’s farm for over two centuries, there is much in it that has been there my whole life, and I never questioned it – never asked why the peonies were pushing up through the foundation of the old barn, why there were poppies in a bramble patch next to a culvert. I never asked these questions of my landscape until I became its steward, five years ago.

Bursting forth from the southeast corner of my house is an ancient, unruly run of old-school lilac bushes. Their blooms reached to my old bedroom window on the second floor, and in my youth, they were gathered by the armful, shoved into every pitcher and pot in my room, hauled to picnics at Maudslay with my friends and given by the fistful to my great-aunt Emily, who would exclaim over them as if we had just discovered a secret treasure, as if she had not been born next to the window that looked out on all of this beauty. Aunt Emily had an endless supply of delightedness with small, natural things brought to her by eager children. It never occurred to me that she was probably also, for her whole long life, remembering her mother.

Philip and Mary Dyer (Noyes) Poore, about 1905.

Mary Dyer Noyes, my great-grandmother, was born in Byfield in 1886. Her own mother died when she was six, and she was raised by her bachelor uncle, the much-loved George Washington Noyes. I do not know how she and Philip Poore met – the families are so intertwined it is likely that they had known each other their whole lives, but when she married my great-grandfather 1905, his pinched face was brightened and softened by her company. Philip was also a motherless child – his own mother died giving birth to him. Perhaps because of this shared loss or because of the steadfast, lifelong love of her uncle, Mary Dyer Noyes Poore was a tender wife and a joyful mother. She was also a fellow breadwinner on a farm that was barely able to feed her growing family, let alone turn a profit. These are the things I know about her from the memories of her six children. She worked all day and often all night, planting, weeding, harvesting, and canning vegetables, caring for six children, and doing all the washing, cooking, and cleaning of a busy, dusty farm. She was always laughing, and she gave her children tricycles and let them ride through the house, and they had an indoor see-saw. She cared more than anything about their education, and she caned chairs late into the night to make a few extra dollars that she could save for her children. And somehow, she read voraciously and was part of an old-fashioned reading club and helped to establish an Episcopal church with the Emery sisters, and even more extraordinarily, from where I’m sitting, she planted flowers.

The lilac at the corner of the Poore house, 1910s.

My great-grandmother died in 1934, just 47 years old. Though the cause of death was pneumonia, Aunt Emily told me that her mother “worked herself to death”. I can only imagine how exhausted she was, what a heavy burden her life must have seemed at times, and yet, she planted flowers. The run of lilacs appears in nearly every posed photograph of her young children in the 1910’s and 1920’s.

The six Poore children and cousin Evelyn Rogers in 1920 in front of the lilacs.

The poppies and peonies in the briar patch by the culvert? She planted those, and every spring, when the plate-size poppies unfurled their papery petals, it felt like a visitation to her children. I never met her, of course, and neither did my mother, and so her poppies remind me of Aunt Emily, the last person I knew who understood deeply what planting these flowers meant to her mother, how they reflected her belief that life and hope would always return.

In April 2020, as I explored my landscape, I was determined to rejuvenate the lilac bushes, a task that I did not complete. The original bushes are over twenty feet tall, woody and gnarled. Suckers spread from its base in waves. I started to dig up the suckers and cut them away as I had been told this would give more energy to the base plant, but with all the sadness and fear in the world, killing something with such a will to live was hard for me. And so, I put out the call. No-contact lilac pick-up, bring your own shovel. And they came, friends and friends of friends and strangers. One such visitor, a woman who grew up nearby on Chase Street, came by. My mom popped out to say hello, and mentioned that our visitor’s great-grandmother Mary, and my great-grandmother Mary, were best friends. "When they finally got telephones, they talked every day", she said. The two great-granddaughters of best friends from a century ago now share this lilac bush.

I love my town, and my house, and the benevolent whisper of the past when you least expect it. And as the lilac blooms fade for another year, I am reminded that hope, and memories, and love, can outlive you. Plant carefully.

1918 West Newbury directory listings for Mary Knowles and Mary D. Poore - a prolific lilac bush would lead their great-granddaughters to meet during the COVID19 pandemic.

The Cushing Contralto Controversy

...a blog by Bethany Groff Dorau

I popped into The Thirsty Whale the other night, my first time back since they reopened. I can’t say I’m a regular, but The Whale features prominently in many of my favorite stories and is where I can reliably run into some of my favorite people.

Which is why it was no surprise that I ran into a friend of mine from my decadent adolescence, who shall remain nameless. And this, dear friends, is the beauty and the sorrow of remaining in, or returning to, the home of one’s youth. In the presence of our teenage friends, we get to be eternally sixteen. We have both changed, my friend and I, but it was the reunion of our old selves – him a Teen Beat-worthy heartthrob, and me a bright-eyed punk rock girl with a jawline that could slice bread. Ah, youth.

And then, while catching up with my old friend, he revealed that he recently worked on the set of the HBO series Julia, about the early years of Julia Child's’ television career. James and I went home and binge-watched all available episodes. I was completely and utterly charmed. Since I am a nerd, I wanted to read more, and because I am a provincial nerd whose loyalty is bound inexorably to Old Newbury, I unearthed a local mystery, a possible subterfuge involving a patrician suffragette, a “luscious” contralto, and Julia Child’s husband. Oh, and some post-mortem landscaping.

Julia Child cooks a hearty meal for the Cushing family - both true and false. Photo credit: Lynn Gilbert, 1978, Wikimedia Commons.

First, Julia. What a gal! Next, Paul Child, her husband. What a guy! They met in Sri Lanka. He was setting up the war room there. And then - imagine the sound of a needle sliding across a record - there was this. From a biography of Julia Child, “their mother, Bertha CUSHING Child moved the two boys and their sister back to Boston, where she had grown up.”

Cushing is a common name, you say. Millions of them. Not necessarily related to the Newburyport Cushing family. You’d be right, and wrong. There are a great number of Cushings in the world, and our branch of the family was not especially prolific. Caleb Cushing himself was childless, as was his niece Margaret, the two people most involved with the Cushing House Museum. But lo, a smoking gun.

The Richmond Daily Times announcement of Bertha Cushing’s Virginia performance. The body of the announcement says, “She is the daughter of the Rev. John Russell Cushing of Boston, a nephew of Caleb Cushing, the eminent jurist”, April 6, 1902

Bertha Cushing Child introduced herself, and was introduced to the public, as the grandniece of Caleb Cushing, at least in early performances. Now, since I collect Newbury connections like some folks collect stamps, I plugged her into my family tree. Well, I tried to. As hard as I tried, I could not make a connection between her father and Caleb Cushing, even as a step- or half-nephew.

I am making this story sound much better than it is. There is no connection between Bertha Cushing Child and Caleb Cushing, at least none after the 17th century that I can find. Bertha may have lied, she may have been passing on a lie from someone else, it may have been a rumor or family story that was repeated until it seemed true. She also referred to herself as a “native of Boston” but was born in Connecticut. What is provable is that she did not claim to be Cushing’s great-niece when she moved to Boston after the death of her husband in 1902 and performed there frequently to support her family.

Bertha Cushing Child and her children, L to R Mary, Charles, and Julia Child’s future husband, Paul. Boston Globe, April 7, 1907

Perhaps it would have been too easy to check her story when in such proximity to the family of her alleged relative. Margaret Cushing, his actual niece, was alive and well in Newburyport and may have objected to the singer claiming such kinship. Perhaps Bertha understood that she would get more traction from a relationship with Caleb Cushing in Virginia.

It is dangerous to guess at people’s motivations, but sometimes putting the pieces together requires a bit of supposition. What the promotion of Caleb Cushing as great-uncle of the singer reveals, beyond a doubt, is that twenty-plus years after his death, Caleb Cushing was still a national celebrity. What is perhaps uncomfortable to consider is that he was also less problematic in the American South.

I am just beginning to do a deep dive into the legacy of Caleb Cushing. He is one of those figures who seems to evoke devotion and anger in equal measure. He was praised by his contemporaries as “the most learned man living”, a brilliant orator, a skilled negotiator, and a pioneer in the establishment of trade and conflict-of-interest rules. He was regarded by many as a highly ethical man.

On the other hand, as Attorney General, Cushing supported the March 1857 Dred Scott decision, which declared that Black Americans were not and could never be citizens of the United States and were not protected by the Constitution. Throughout his political career, Cushing opposed the abolition of slavery and supported states’ rights, though he supported the Union during the Civil War.

In 1874, President Grant nominated Cushing as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. His nomination was withdrawn when Cushing's friendship with President of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis was made public. His withdrawal from nomination was explained away by his supporters as “purely partisan”, but it is pretty damning. Cushing wrote a letter of recommendation for a member of his staff directly to Jefferson Davis, already the leader of the burgeoning Confederacy, on March 23, 1861.

The New York Times, page 1. January 14, 1874.

Though this could be explained by a long-term friendship between the two men, President Lincoln had issued a proclamation prohibiting communication with the rebel leaders, and Cushing clearly and knowingly violated it. The New York Times declared the “DOOM OF CALEB CUSHING” and published a summary of the “TREASONABLE LETTER OF MR. CUSHING”. President Grant quickly withdrew his nomination.

It is fascinating from a distance of over a century how people are lionized, vilified, excused, and excoriated in the public mind. But we know that at the dawn of the last century, Caleb Cushing's name was enough to help launch the career of Julia Child’s mother-in-law, who Julia referred to as “an utterly impractical, pre-Raphaelite creature”. And the post-mortem landscaping? Bertha Cushing Child died in Paris in 1933 and her ashes were interred at Père Lachaise Cemetery. Since her grave was leased, not owned, however, after 30 years, her ashes were sprinkled on a lawn.

I am a little bit sad that my plans to recreate the Julia Child kitchen at the Museum of Old Newbury in honor of her family connections here are dashed. I did so want to think of Paul Child as the urbane, witty heir of a long line of Newburyport folks. Plus, if he had been Caleb Cushing’s great-great nephew, Julia Child would have been my sixth cousin-in-law, and THAT would be worth boasting about.

After all, I have followed Julia's advice closely, at least when it comes to history. “Find something you're passionate about and keep tremendously interested in it."

A New Look for Old Newbury

by Bethany Groff Dorau

The poster for this year’s 43rd annual Garden Tour reveals a new element to our evolving identity at the Museum of Old Newbury. In August 2021, the museum contacted Matter Communications, a public relations, social media, and creative services firm, to explore a refresh of the look of our materials. It started off with a simple request – I needed business cards and stationery, and it set off a search for a logo.

The Museum of Old Newbury, like many venerable institutions, has a complicated identity based on a century and a half of evolution. Matter had shepherded Lowell’s Boat Shop, the Custom House Maritime Museum, and other respected colleagues to new and refreshed brand identities, and I was hoping that they would have some ideas for us as well.

My first contact at Matter was an old friend who works in a different branch of the company than the one that could help me with a logo. She sent me to a colleague. The whole thing seemed quite simple – invite some creative people over, show them some cool stuff, and voila…a logo. First, we went on a hunt for past marketing and branded materials. They were legion.

Our legal name is still, and will likely always be, the Historical Society of Old Newbury. Our official letterhead bears that logo – squarely based on their interest in the early years of European settlement. The year of settlement is at the top of the seal, the date of the founding of the Historical Society is at the bottom. There are not one but two people brandishing weapons, a view of a castle, and another of ships in the harbor. It is laden with meaning, with elements that spoke volumes about who the organization was in the first years of its founding, and who they wanted to attract. Aside from some problematic imagery, there was little about this logo, aside from the ships in the harbor, perhaps, that spoke to who the Museum of Old Newbury is today, and who we want to be in the future.

We also had a logo that featured just the Cushing House, others that represented elements of the garden. We had been known as the Hist, 98 High, the Cushing House, The Society, and MOON, among other things. It was a delightful walk-through time celebrating generations in the life of this place I love.

The Matter team came to the museum, and during our conversation, it became clear that this would not be a simple matter of popping some compelling image onto a business card. We needed a deeper dive into who we are.

So, who are we? Our mission statement says what we do, and it is a good place to start, but who are we to our members, our visitors? What do we have that sets us apart? We preserve significant elements of the collection of the Newburyport Marine Society, along with centuries of other maritime history. So, a ship? But wait – the key elements of our collection are just that – the collections. So, a silver spoon? A pewter flagon? A chair? A figurehead? Detail from important local wallpaper? But wait – don’t people really identify us with the wonderful architecture of the 1808 Cushing House? And what about the years, decades, even, of work that has been done on the garden and landscape? Our peach orchard used to be world famous.

This is when you realize why, like so many other professions that look like “fun”, branding and marketing are hard work. Matter took it all in, ran it around in their considerable brains, and gave us some options and some reasons why those options could work for us. In the end, the logo you see represents four elements of who we are. The ship, of course, represents our maritime heritage and collection. The wisteria represents a recognizable element of our landscape (those of you who have ever had to fight with wisteria may wish we had chosen differently). The flagon represents our incredible collection of objects from Colonial Newbury, particularly affiliated with the church, and the Cushing House is our home. Any of these images can be called out and used individually, but as a group, they speak to what we have to offer. And as a group they represent a window, a window not only into our past and the history that built this community, but it also represents a window into what comes next for our growing and evolving community and the role our museum will play. Because after all, a window goes both ways.

Selection means elimination, and there are numerous elements that we wish we could have included. One logo idea featured the weathervane from the First Religious Society, an iconic rooster. In a logo, however, it did not work as a representation of the museum. The image on the most recent run of business cards, and on the sign outside, was Triton, a remarkable maritime figure discovered during a harbor dredging operation. Known affectionately as the “Merman”, he is an amazing artifact, but rendered in miniature, he is difficult to place. There is nothing that speaks explicitly to our incredible art collection and archive.

The museum will change in the decades, and with any luck, centuries ahead. We will continue to search for the best ways to communicate with our friends old and new. In the meantime, beginning on June 2, you can come see it all for yourself. Buy tickets here.

The 1950 Census - a quick how-to

by Kristen Fehlhaber and Bethany Groff Dorau

A few of the occupations listed by 1950 residents of Fair St and Orange St in Newburyort.: brander at a radio tube factory, payroll clerk at a shoe factory, telephone operator, and floor sweeper.

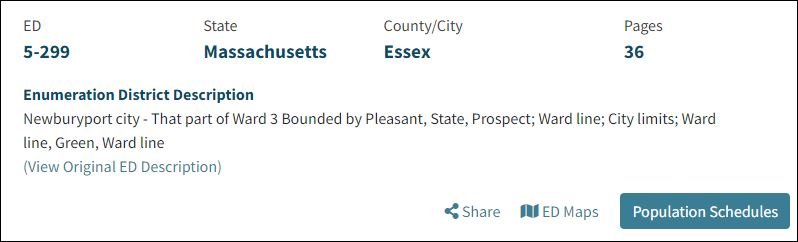

On April 1, the 1950 U.S. Census was released. It’s completely free and available from the U.S. government at archives.gov. Indexing isn’t complete yet– if you know the name of a family and their location in 1950, you can try to find them, but you might strike out. So at this stage, many people are scanning the census by location. The census was broken down by state and county and then by Enumeration District (referred to as ED going forward). For a city like Newburyport, each ED was drawn to have no more than 1000 people in it. In rural areas, EDs might have a up to 1400 people.

To look at Newburyport, you can a see a map of the 1950 EDs here: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/12171739.

If you’re looking for West Newbury, the EDs is 5-477 for the western part, 5-478 for the eastern part, and 5-479 for the boys’ orphanage at the current Page School. For Newbury & Byfield, look in ED 5-289 (east of Rt. 1 and Plum Island) and 5-290 (west of Rt. 1). The first page you’ll see is a card summarizing the number of people in the ED. Scroll ahead to see the pages detailing the residents. Newburyport was still full of manufacturing at the time – occupations are listed on the right hand side.

Wondering about the Museum of Old Newbury home at 98 High Street, we clicked on the Newburyport ED map and located the northeast corner of High St. and Fruit St. in ED 5-299 (we added an “X” there).

To see the census records for all the residents of 5-299, follow this link and click on Population Schedules (the button in the lower right corner).

Moving to page 2 of the 36 pages of this district, we see 98 High Street as the first household recorded – lucky us! Streets are written vertically along the left-hand margin.

Margaret W. Cushing is the first person listed, age 95, never married. Below her is Mary M. Driscoll, lodger, age 66, also never married.

Scrolling to the right, we see more information about Margaret Cushing and Mary Driscoll.

Sometimes the census can shed some light on how people described themselves, which can be very useful to a researcher. For example, Mary Margaret Driscoll, who went by Margaret, is described as a “registered nurse”, which is then crossed out and “lodger” substituted. This is likely an error on the part of the census-taker, as her occupation appears in another place on the form. This is where it gets interesting. Though she is described as a lodger, rather than “maid”, the only obvious category for a female employee, Margaret Driscoll clearly believed herself to be employed by Margaret Cushing. When asked what she was doing for most of the previous week, she said she had worked 84 hours, or 7, 12-hour days as a private nurse in the home.

Margaret Driscoll seems to have come to the Cushing household in the mid-1920s to care for Margaret Cushing’s older brother Lawrence, who died in 1933. An article published upon the occasion of Margaret Cushing’s 100th birthday notes that “Miss Margaret Driscoll, R.N.” was unable to attend as she had died one month before. She is described here as Margaret Cushing’s “nurse-companion” for 30 years.

In the years that Miss Driscoll spent with Margaret Cushing, and in the years since, she was described as a “companion” to the older woman, a title that has come to mean something slightly different than it did in the past. At the time, it was somewhere between friendship and employment, a genteel way of blurring the lines between equality and servitude, but Mary Margaret Driscoll’s answers to the census takers tell us that she clearly thought of herself as employed by Margaret Cushing and described all her long days in Margaret’s company as work. This does not detract from any warm feeling these women may have had for each other. The newspaper article notes that she is “missed from the pleasant event.”

Article on Margaret Cushing's 100th birthday. Newburyport Daily News, page 6, February 10, 1955.

We hope you'll take a look at some of these census records – there is much to be learned. And if you discover something interesting, please share it with us at info@newburyhistory.org.

Chasing Duncan

by Bethany Groff Dorau

I was having lunch at the Grog recently, when my companion pointed to the portrait of a sea captain that hangs over the fireplace. “Who do you think that is?” she said, taking in the white beard, the nautical cap, the sparkling eyes. “That be Duncan Chase,” I said in my best fake pirate voice. “Ooh,” she said, trailing off…”Captain Chase.”

Duncan Chase, painting by Jim MIckelson courtesy of The Grog restaurant

Well sort of, though he answered to Colonel. I told her what I knew of the man – he was drunk all the time, and he was tall and loud. He told people he spent the winter in Cal-E-Fornia. He was a panhandler, meowing loudly at tourists and friends alike, usually wearing a jaunty scarf around his neck. After he died, he was given a plot and a headstone at Old Hill by kind Newburyporters.

My friend had questions. Was he born in Newburyport? Was he from the old Newbury Chase family? Where did he sleep? Why did he drink? Was he a veteran?

History, or historians at least, abhor a vacuum, and so I began to fill in the gaps. Maybe he was once in the Navy, I said. Seems the right age for World War II or Korea. He was probably the black sheep of an old Newbury family, returning from the war with a legacy of trauma and…hold the phone. I reeled it in. I had veered dangerously away from facts, or even rumor or memory. “I’ll see what I can find,” I said, and then forgot all about it until a few days later, when I ran into his headstone while looking for someone else. That’s two Duncan Chase sightings. And then I was looking up Chase & Shawmut online and up popped this picture of Duncan. That’s three. I can take a hint.

Duncan Chase, photo by Robert Atwater, mybigphatphotographs.com

I know right away that this was a picture of Duncan Chase passed out in a doorway, a bottle of whiskey in a paper bag next to him. I even thought I knew which doorway. I remember him there. I remember his signature call to passers-by, “I’m a cool, cool cat from NEW YORK CITY”. I contacted the photographer to ask permission to use the image. He kindly agreed.

And then it started to bother me – not the image, which was an accurate portrait of the man, but my lack of concern about it, my willingness to share it without context. To me, Duncan Chase was not a man worthy of my professional due diligence, but a caricature, a symbol of the town drunk, some charming relic of bygone old Newburyport who had become, in memory, one-dimensional.

And then I did the math. Duncan Chase and I never met. He died in 1980, when I was six years old and living in Canada. I knew him only from the stories I had been told. Maybe his ghost was in that doorway when I was hanging out at Inn Street, but the flesh and blood was long gone.

So I began at the end and worked my way back. I found his death record, then his birth record, then his parents’, then, voila, his paternal great-grandmother, Jane Merrill, already in my family tree. With a satisfying click, I added Duncan to my tree, watched his ancestors and mine match up and dance around. He settles in as my sixth cousin, once removed – one more piece of information that is about me, not him, really, but it gives me a place to start.

Duncan Howard Chase was born on Chestnut Street in Groveland on October 19, 1919, the youngest of four children born to Raymond Chase and Charlotte (Buxton) Chase. Duncan’s parents met in Haverhill and married young – Charlotte was just 16, Raymond was 22, and though both could read and write, neither had a high school education. Duncan’s father Raymond worked at a Haverhill shoe findings shop. At some point between 1930 and 1935, Charlotte Chase left her husband and moved to Newburyport with teenage Duncan, who had left school after 5th grade. They lived in a small apartment on Washington Street, then another apartment on Fair Street. She is listed as a sewer, working for the WPA, then a dressmaker, later a “practical nurse”, or uncertified health aide. It is possible she chose to come to Newburyport because her brother Myron Buxton was already here, listed in the 1931 directory as living on Kent Street with their mother. By 1937, Duncan Chase’s mother, uncle Myron and grandmother, Lenora, were living at 2 Orange Street, and it was this address that Duncan gave the police when, in 1939, he was apprehended in Florida for forgery, check larceny, and stealing a car from a Newburyport shoe factory foreman. He spent two months in jail, got out, worked as a laborer for Oscar Traister for about a year while stealing more checks, and then took off with another car.

Newburyport Daily News, Thursday, December 14th, 1939

This was the end of the line for Duncan’s family. His mother informed the newspaper in October 1941 that Duncan Chase was no longer at 2 Orange Street. When he went before a Salem judge in 1942, he promised to join the army “if he can be accepted.” He had nowhere else to go. The judge was encouraging. “You might make a record for yourself in the army. You might get the Distinguished Service Cross.”

Duncan Chase never entered the army. Two years later, he was sentenced to two years in prison for grabbing a woman’s purse on Bartlett Mall. In 1946, when Chase was 27 years old, he was arrested for breaking into his mother’s house on Orange Street and stealing his brother’s knife and shoes. It was the first time the record cited alcohol as a contributing factor.

In 1949, Duncan Chase and Hilda Olsen Carpenter were married in New London, New Hampshire. She gave her occupation as waitress, his as handyman. It was his first marriage, her second, and was over within a year. The next two decades were a slow slide into homelessness and addiction, and Duncan was repeatedly arrested for drunkenness and petty theft, unable to make bail, and veering between prison, locked hospital wards, and the streets of Newburyport and Haverhill.

By the time I was born in 1974, Duncan Chase had become one of the notable “characters” of Newburyport. In a nostalgic Boston Globe article, Jeremiah Murphy opined that “Old Newburyport is my kind of city,” while “Duncan Chase is still hanging around Market Square, except for an occasional vacation at the expense of the county. Almost every town has a Duncan Chase.”

Recently, the number of people living on the streets in American cities has sparked a heated, and recurring, debate. Some argue that unhoused people with addictions and mental and physical challenges should be placed in guardianships, effectively ending their rights to self-determination and legal adulthood. It is a thorny issue, with civil rights advocates arguing that the right to live on the fringes of society, to be weird, and make mistakes, and yes, even to drink too much and sleep on the ground if one chooses, should be protected. It is a slippery slope, they say, and once a person is placed in guardianship, it is extremely difficult to get back out. For others, the human rights issue is that those who most need help are least able to get it, and so someone else must advocate for them.

I do not have the answer. I could convincingly argue both sides of this issue. As for Duncan Chase. I do not know why he drank – he may not have known himself. Most people who met him have a story, and most of these stories are about how funny and charming and interesting he was. But there are others. He was frightening when he was angry. He would destroy things – break store windows and throw bottles to get locked up so he could have a place to sleep. Sometimes when the weight of his life settled in on him, he sobbed inconsolably. Some wish that there had been more intervention in his case. Others feel that he lived exactly as he chose and find nobility in that.

Duncan Chase is buried at Old Hill Burying Ground, the plot and stone paid for by his friends.

What I believe is that everyone, living or dead, deserves to have the truth told about them, so far as we are able, and that Duncan Chase, like all of us, is a complicated person, not just a picturesque symbol of old Newburyport, but not just a figure of pity either. The next time I look at a picture of him, all blue eyes and white beard, over the fireplace at The Grog, I will tell a truer version of his story, including the truth of the untrue parts. He was not from New York. He did not spend the winters in California. But he was a cool, cool cat.

Previous Blog Posts

Classic Smith-Corona typewriter

Previous blog posts (Summer, 2021-March, 2022) can be found linked on this page.