The Good, the Baud, and the Ugly, Part II: John Atkinson and the Merry Widow Stickney

/a blog by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

This is Part II in a series. For Part I, see here.

Well, friends, you will all be happy to know that I survived the week, despite my titillating revelations about the venerable Atkinson family. I did fall off a ladder, so I leave you to wonder if Mae Atkinson has taken her revenge after all. To be fair, it was a rickety old step ladder, and I am not the sprightly waif I once was. Still, once one has decided that there might be a member of the spirit world with a chip on their shoulder, almost anything becomes suspicious. Look – I just summed up the whole plot of The Crucible! Incidentally, there is a superb performance of The Crucible being performed this weekend at the 1785 Rocky Hill Meeting House. Get tickets here.

But I forge bravely ahead. There are more scandalous tales to tell. When last we left the merry Widow Stickney, she had taken John Atkinson to court for fathering her child, a daughter named Mary. The town was divided on the veracity of her testimony, and dozens of people showed up at the Essex County Quarterly Court session to offer their take on the situation.

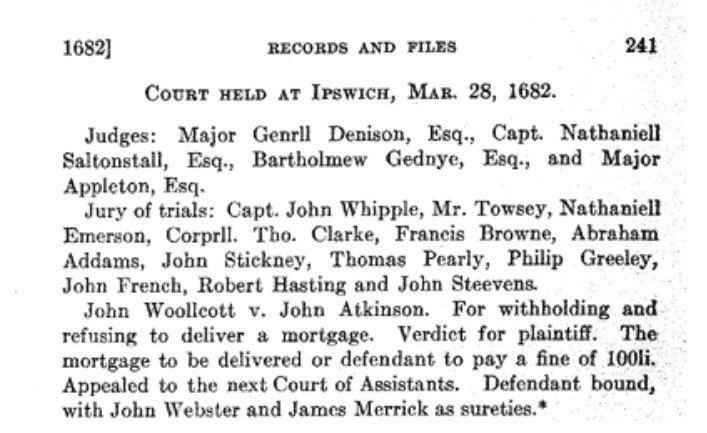

At the March, 1682 Ipswich session of the Essex County Quarterly Court, in which John Atkinson denied that he was the father of Widow Stickney's daughter, he is the first case on the docket for another matter - refusing to return a deed after a mortgage he held was paid off. He was found guilty.

There were other possible fathers for Widow Stickney's baby, Atkinson argued. Sarah Stickney had been heard accusing Samuel Lowell of fathering her child, including once near the birth of the child. Lowell himself was ready to step up and promised to bring his new daughter “wittles and clouts”, or swaddling clothes. A third lover for the Widow Stickney was revealed to another witness, who had seen James Merrick (John Atkinson’s brother-in-law) sneaking into her house at night. For those of you keeping track at home, this would indicate that Sarah Stickney, mother of nine, had three lovers going at one time in 1680. Where did she find the time?

Sarah accused John Atkinson of slander. John accused Sarah of slander. They were both found guilty. Neighbors testified that John had started being very nice to anyone that might witness against him, settling old debts and mending literal and figurative fences. Despite this, John was found by a jury to be the father of Sarah Atkinson’s child and was ordered to pay “12 shillings for the jury, 8 pounds for the past maintenance of the child, and 2 shillings, 6 pence per week until further order of court.”

John went away mad but was back in court soon for beating Sarah with his walking stick “so that her child fell almost into the fire”. Her uncle and brother were witnesses and John Atkinson was ordered to pay a 26 shilling fine. This did little to cool his temper, and two months later, he was back in court.

The c. 1664-1665 Atkinson House at 5 Hanover Street in Newbury. From “Old Newburyport Houses” by Albert Hale, 1902.

“John Atkinson of Newbury, being the reputed father of Sarah Stickney’s last child, complained that he was hard put to it to pay all charges, and court ordered that half of his payments should be in money and the other half provisions or clothing for the said child at money price.”

Four months later, he was back yet again, arguing that there was a shortage of money, and he should not have to pay so much, and besides, he should only have to pay half since he was only one of two parents.

“I cannot think it is the mind of the Court that the whole maintenance of such a child should be put upon a reputed father (it is evident it is hers, & therefore hath just reason to bear half) whereby ye maintenance of such a child should arise to be double what others pay.” He also revealed that Sarah had been pregnant once before in her widowhood and had threatened a paternity suit (there is no proof of this), and if she was continuously granted child support, it would be “a precedent to induce such persons to commit lewdness when by their accusation they can force on wealthy persons and get increased income”.

John Atkinson already had a wife and nine children of his own, and argued that paying the full amount would make him a pauper. He demanded custody of the child, so that he would not be “kept a continual slave to her who hath injured me, and Impudently and scoffingly insulteth me.”

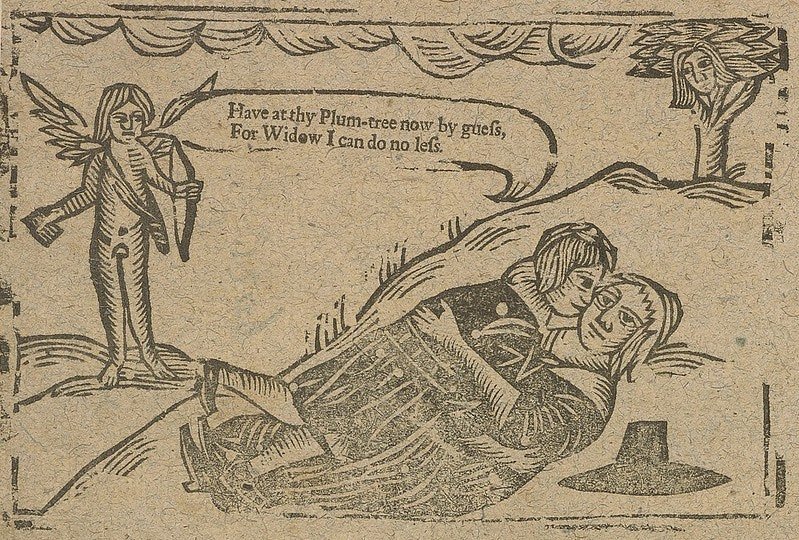

The voracious widow was a popular subject of ribald ballads published in England in the 1680's. This illustration is from The Hampshire Miller, sung to the tune of A Languishing Swain.

Atkinson understood the law, as he was a frequent participant in it. In addition to the fornication case, in 1682 alone he was in court numerous other times for various reasons, accused of swindling his neighbors, accusing them of swindling him, witnessing in a forgery case, and more. He understood that the court’s interest was in the support of the child, not the parental rights of Sarah Stickney. If he could find another solution that did not involve him paying her, and did not leave the child without support, the court would likely honor his rights as Mary’s father, which, after all, Sarah Stickney had taken such pains to prove.

There is scads more scintillating testimony, including one memorable scene when all of Sarah Stickney’s lovers get together and draw lots to see who would take responsibility for the pregnancy. John Atkinson drew the short straw. Furthermore, Sarah Stickney seems to have been a bit of a moral relativist, telling James Merrick that she and Samuel Lowell knew their lovemaking was a crime, sure, but so was smoking a pipe in the street, and one was “no more a sin” than the other.

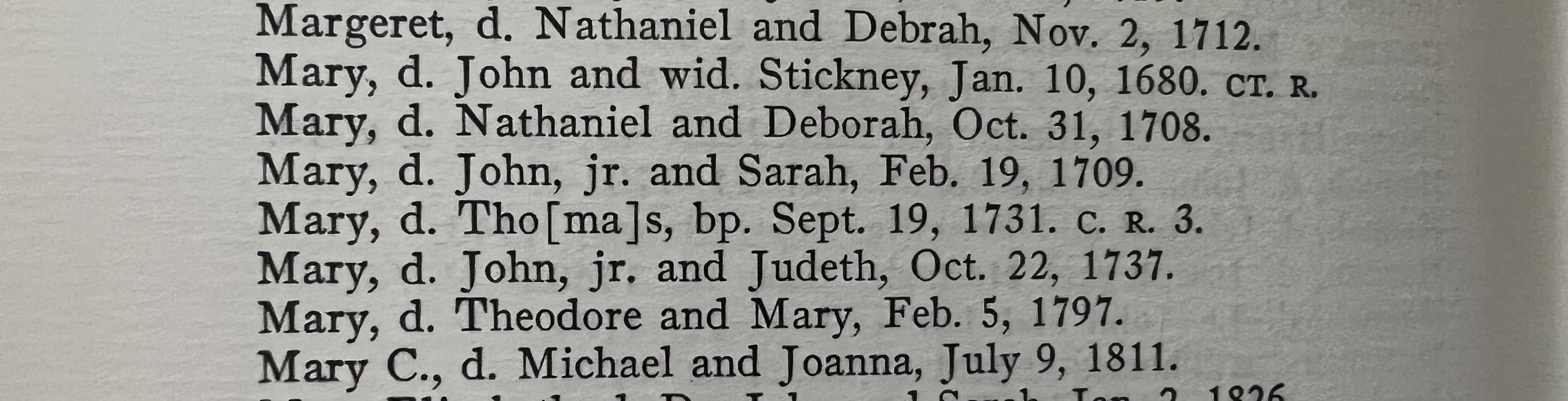

The court did not free John Atkinson from his paternal responsibilities, but they did the next best thing. They told him that he could have the child and give it to someone else to raise. Perhaps the court knew that Sarah Stickney would never let this happen. John Atkinson certainly knew it. If Sarah didn’t give him the child, she was to “maintain the child at her own cost”. The child’s name was entered into the birth record as Mary Atkinson, born January 10, 1680.

Mary's name as recorded in "Vital Records of Newbury Massachusetts, To the End of the Year, 1849; Vol. I - Births."

And then all hell broke loose.

Join us in the next newsletter when John Atkinson threatens the Newbury town clerk, buys a mad cow, and steals pork and barley from widows and orphans. It’s not all fun and games here in Old Newbury. John Atkinson is also about to take part in the murder of an innocent woman.