The Good, the Baud, and the Ugly, Part III: John Atkinson and the Merry Widow Stickney

/by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

This is Part III in a series. For earlier posts, see Part I and Part II.

Picture it – yours truly, rising slowly from her seat on a cold meetinghouse bench, pointing to a robed figure high in a pulpit against the meetinghouse wall. “You are deceived, sir,” I say. “You…are…deceived.” There is death spreading its wings over the room. There is screaming, spitting, lies, courage, and love, all in one moment in time. One moment when things could have gone another way.

Amesbury's 1785 Rocky Hill Meeting House was aglow for evening performances of Arthur Miller's “The Crucible.”

This happened last week. I was called upon to speak the parts of both Rebecca Nurse and her husband Francis in The Crucible at the Rocky Hill Meeting House in Amesbury. I would do just about anything for Edward Speck of Theatre in the Open, so when he held out the binder to me festooned with a clip-light and said “surprise”, just before the performance began, I thought, “how hard can it be?” It was crushingly hard.

Morgan Amelia Fanning as Abigail Williams in Theater in the Open's "The Crucible" at Amesbury's Rocky Hill Meeting House.

I had just spent a good portion of the day preparing for this story, you see. I had teased with a John Atkinson link to murder and witchcraft, and I had spent some time looking at ancient records, death warrants, physical examinations, pleadings. It is wonderfully satisfying to see these words in print, to connect original records to people I know, but sometimes it rends the veil, and an icy finger comes through the page and pokes you in the throat.

This was the document that did it.

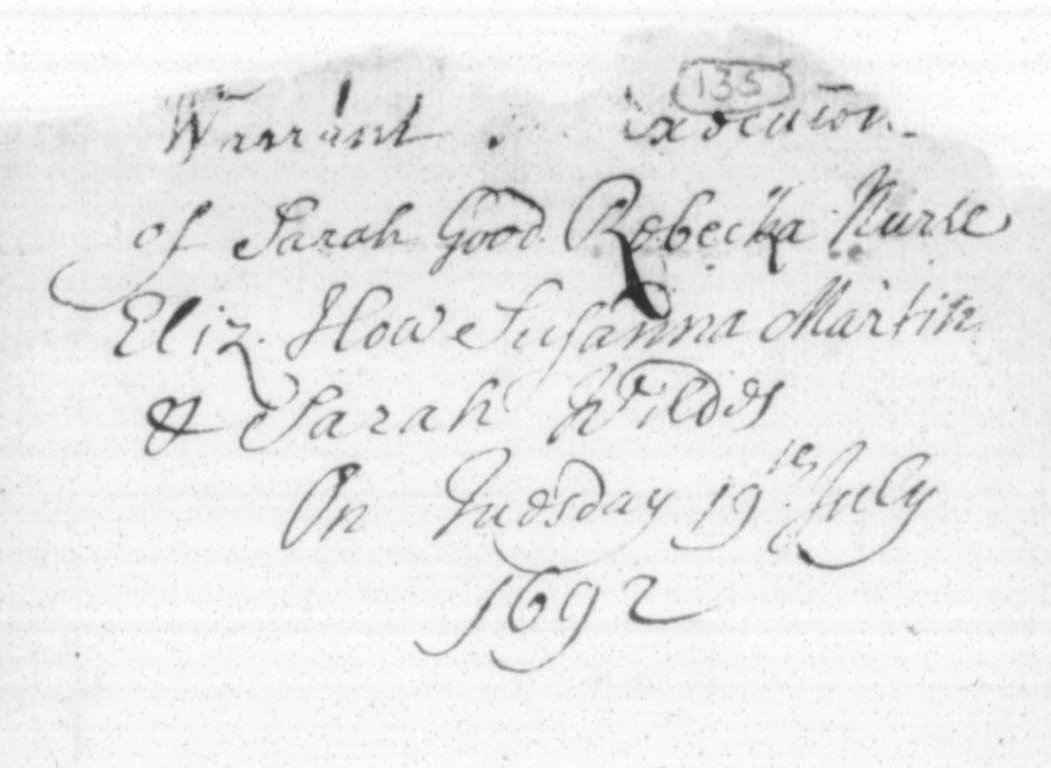

Death Warrant for Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Elizabeth Howe, Susanna Martin and Sarah Wildes. From wikitree.com

This is the warrant for the execution of Sarah Good, Rebecca Nurse, Elizabeth Howe, Susanna Martin, and Sarah Wildes. Pause for a moment and consider Susanna Martin, a 70-year-old widow from Salisbury. The testimony against her is excruciating to read, and two of her accusers were John Atkinson and his wife Sarah.

John Atkinson found evidence of witchcraft in the purchase of a cow that behaved badly. “I went to the house of Susanna Martin to receive the cow of…her son. When I came to bring the cow home, notwithstanding the hamstringing of her and haltering her, she was so mad that we could scarce get her along but she broke all the ropes fastened to her…When we came down to the ferry, we were forced to run up to our waists in water, she was so fierce, but after with much ado we got her into the boat, She was as tame as any creature whatsoever.”

John Atkinson's testimony about his disobedient cow helped to sentence Susannah Martin to death in 1692.

Sarah Atkinson’s testimony was more damning. “Some time in the Spring of the year about Eighteen years Since, Susanna Martin came unto our house at Newbury from Amesbury in an Extraordinary dirty Season when it was not fit for any person to travel. She came on foot...I asked how She could come in this time on foot and bid my children make way for her to come to the fire to dry herself. She replied she was as dry as I was...I could not (see) that the soles of her Shoes were wet. I was startled at it that she should come so dry and told her that I should have been wet up to my knees if I Should have come So far on foot. She replied that She scorned to have a drabbled tail.”

That’s right. Eighteen years before, Susanna Martin failed to get muddy enough on her way from Amesbury to Newbury, and this, and other incidents equally mundane, were enough to have a woman murdered in 1692. It took great courage for Francis Nurse to stand up to the judges and look them in the eye and tell them that they were deceived. It could have cost him his life.

But all this ugliness was still a decade away when John Atkinson and the Widow Stickney duked it out in the Essex County Quarterly Court in 1682, when John Atkinson was found responsible for fathering Mary, the daughter of Widow Stickney. Incidentally, John Atkinson was in court in Ipswich for that session answering a variety of charges, including that he had tried to swindle the impoverished Woollcott family out of a piece of land for which they had paid him in barley, pork, and coin.

But back to the Stickney trial. Mary’s birth was entered into the Newbury town records as Mary Atkinson. After some contentious back-and-forth, John Atkinson landed on a solution. He would take responsibility for the child but find someone else to raise her. The court agreed and ordered that John would be freed from his weekly child support payments once he had found an appropriate family to give her to, but “in no case was he to keep the child at his own house. Should Sarah (Stickney) not deliver the child to the place he provided…she was to maintain the child at her own cost.”

John Atkinson went to Widow Stickney’s house to collect the child. Stickney told him to go pound sand, thereby giving up her right to child support. Atkinson then enacted part two of his plan. Having rid himself of responsibility for paying for Mary, he went after the Newbury town clerk. The court, rather unexpectedly, sided with Atkinson. “(Upon) being informed that the clerk of the writs of Newbery had entered the bastard child of Sarah Stickney of Newbury in the records of births as the child of John Atkinson, upon whom she charged it, although he did not own it, it was declared to be a high irregularity, and the clerk was ordered to appear at the next Ipswich court unless he give satisfaction to said Atkinson before that time.” The clerk was ordered to remove Atkinson’s name from the record, though he seems not to have done so.

The court was clearly ambivalent about the entire situation. They allowed John to petition to remove the “Atkinson” name from the child’s birth record but took a bit longer to relieve him of child support, since he had failed to find another placement for the child. In October, 1682, John’s wife Sarah tried her hand at petitioning the court. “(I have) been sorely troubled and perplexed by reason of the troubles falling upon my husband John Atkinson, which have been very changeable and vexatious by reason of the imperious dealings of Sarah Stickney…threatening and scoffing…so that mine and my children’s lives are wearisome to us, who cannot go up and down quietly, but meet with that which is grievous to us.”

The court extended the payments to Sarah Stickney to April 10, 1683, and if Widow Stickney had not handed over her daughter by then, all support would cease. Despite threats and cajoling and a serious financial motive, Sarah chose to raise her daughter alone, at her own expense.

The Merry Widow Stickney was not alone for long, however, marrying Stephen Ackerman (also spelled Acreman or Akerman) on December 17, 1684. They had two more children together, bringing the Widow Stickney’s kiddo count to at least twelve.

The Morse/Stickney/Ackerman/Atkinson dinner table, perhaps? Ballad print c. 1670, Courtesy of the Bodleian Library, Oxford

As for Mary (probably Atkinson) Stickney? She stayed with her mother until, at age 20, she married Daniel Poore Pettengill. Whatever the controversy of her youth, she honored the father she had known since she was five years old, naming her eldest son Akerman Pettengill.

The last laugh may be reserved for the long-suffering Newbury Town Clerk, in the end. Under Atkinson, we find the following entry into the transcribed Newbury Vital Records.