How to Photograph a Garden

... a guest blog by Bob Watts, MOON Board member

I was my Mother’s first born…. born in early June when summer was approaching full swing. She always remarked how much she loved her red rose bush, climbing up the screened-in porch. The beautiful fragrance always reminded her of my first days. We have this one photograph and I treasure it…. made 60 years ago in New City, NY (a hamlet of Clarkstown, Rockland County).

I’ve been asked to share my best tricks for how to photograph a garden. You can use your camera phones or digital cameras - both can make for beautiful images.

Start with a general view - the entrance, a gate, a path. Think about the view the gardener hoped you would first see. This is an inviting garden gate from the 2022 Garden Tour with the roses at peak bloom!

Next you may be offered a full, sweeping view of the garden - this might be a nice horizontal view. Look for something of interest (flowers) to fill the bottom half of the image. This is where a wide angle setting on your lens choice could work well. Phones have a wonderful shooting mode called “Panorama”. Make it with your phone in vertical position and it’s not necessary to create it to be a full 180°, just swoop enough to get the full expanse of the garden.

Look for where the gardener means for you to spend some time. We at the Museum know that Margaret Cushing would sit and gaze upon her garden from the "summer house," which is still in place. This view should fill your frame and remember that vertical can work well, all dependent on the subject. (Filling the frame is a good general tip on almost all images.)

Next you can explore views from this spot.

Take a look at this bird bath. A straight-on image works but I prefer the one where I stood on my toes to look down from above. It gives a better view of the water plants and their beauty.

There will be the ever-changing palette of the various plants and flowers. Some tips:

Get low to be at the level of the bloom

Try a zoom/telephoto setting - you might need to step back (remember “fill the frame”)

If you can control the lens opening, use a wider open aperture so that your depth of field is low and flowers in the background go out of focus. On your phone, you can get this effect in the “Portrait” setting.

Get above and in tight to fill the frame

I love to look for special objects in the garden. Mirror balls or gazing balls go back to 13th century Venice and were used in royal gardens throughout Europe. I love the fun of them and this became a favorite “selfie” image with my daughters.

Just remember…. you are creating a historical record for the generations to come. It is a lovely gift to the future. Here is a favorite from the 2022 Garden Tour - the gardener and his view of his creation.

Come for a garden walk with me….

Cheers,

Bob Watts

Let's Call It October

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

For the past nine years, on the last weekend in April, I belong to the Newburyport Literary Festival, body and soul. Ghlee Woodworth and I were brought onto the steering committee for this event in 2014, after local history was spotlighted and we were identified as two purveyors of such heady material. Also, between Ghlee’s boundless energy and my passable tech skills, we make a good team.

Ghlee and I, local historians and Lit Fest buddies at Newburyport City Hall.

And so, after months of meeting, spreadsheeting, cajoling, arranging, and preparing, on the Literary Festival weekend, with a limited degree of success, I run a projector at City Hall, or a Zoom webinar in my guest bedroom. I try to remember to hydrate, to speak slowly, to pronounce names correctly. And, blessed beyond measure, I am immersed in the world of writers and readers. We float through the rare air of downtown Newburyport, thinking big thoughts and seeing everything anew. At least, that is my experience.

I am brought to tears every year at least twice – in the best way. And I am given a gift – some idea or turn of phrase or interaction that remains with me. This year, our first year back together in person since the beginning of the pandemic, the first gift came quickly. It was Friday night, and we were at the opening event at the Firehouse. Our own Andre Dubus was on stage talking with his friend Peter Orner. Orner read a short story from his new book, a memory of his mother at the sink washing dishes as Nixon takes off in a helicopter.

“I don’t know what month of 1974 Nixon called it quits. I could check. It’s exhausting being able to check anything and everything. Let’s say it was spring, late spring, when Nixon resigned.”

I instinctively bristled a bit. “Let’s say…” is not a way to go about writing about something that really happened, says the historian in me. Nixon resigned in August, 1974. But, of course, that was not the point.

Peter Orner (above) and Andre Dubus opened the Newburyport Literary Festival this year; Peter spoke about his new book, "Still No Word From You."

Memory is slippery and subject to change as we remember the last time we remembered, an endless loop that, without a certain amount of anchorage, can spin off in all kinds of directions. But an essential element of memory is its changeability – its willingness to be informed by later experiences, to adapt to new information. Of course I want to know a true thing, but the true thing may be that the day Peter Orner watched his mother at the sink, it FELT like late spring.

And so, I did a little experiment with a memory of my own.

Let’s call it October. I am sitting at the kitchen table with my great-aunt Emily and my grandmother, who is in a wheelchair, and their brother, George, who is talking in gasping grunts about going to the hospital to have shrapnel removed. I ask Aunt Emily what that looks like. It’s terrible, she says. Like bits of metal and machine parts and things, always working themselves out of his legs. She says she once saw them remove a spring, part of a hand grenade that blew up behind him. He is missing a finger and most of one foot. He has a glass eye, but he has taken it out, and the hollow socket is red. His hair is shaggy, longer than any of his brothers, and he likes to look at me with his one milky eye, take off his cap, and thunk thunk on the metal plate on the back of his head with his knuckles. “Guam”, he says. He points to his eye socket. “Okinawa”. I say something and he cups his hand around his ear. “What?”, he shouts, then points to his deaf ear. “Midway,” he says, and laughs, his toothless mouth another socket in his wide, grey face. He is shifting his considerable weight in his chair, the sturdiest chair in the house, and over the years, his large, flat thumb has rubbed the end of the chair arm until a spoon has formed. He drinks, though there is no alcohol allowed in the Poore house, so he arrives drunk from his apartment in Newburyport. He dozes off, and he smells of mildew and cigarettes and liquor. I am scared of Uncle George, and I feel sorry for him, and I leave the room as soon as I can.

George Allen Poore’s military hospital record validates my memory of him.

Diagnosis: Wound(s), penetrating (point of entrance only: includes incised, puncture or stab wound) with nerve or artery involvement;

Location: Eyeball, generally;

Location: Metacarpal bones, generally;

Causative Agent: Artillery Shell, Fragments, Afoot or unspecified;

Diagnosis: Fracture, compound;

Diagnosis: Wound(s), penetrating (point of entrance only: includes incised, puncture or stab wound)

Type of Injury: Battle casualty

Medical Treatment: Enucleation with implantation; Amputation open, upper extremity, (includes amputation, unqualified, for traumatism)

Disposition: Discharged or Retired for Disability, Line of Duty, YesBut there was another gift that I was given because of the Newburyport Literary Festival.

Colleen and Frank Stiriti, whose new book Images of Life, Change & Beauty: Photographs, Poetry & Art - Selections from the works of Fran Dalton was the focus of one of the sessions at the festival, gave me these pictures of Uncle George, found in two envelopes marked “Mr. George Poore” in Fran’s distinctive hand. Uncle George, who I remember with such trepidation, was photographed with a palpable tenderness by Fran Dalton, whose experiences as a trans woman certainly informed her appreciation for outsiders and loners. She had endless empathy for the wounded.

There are almost no family photos with Uncle George in them after 1970. To many of us, he had become unlovely. But through Fran’s eye, through Colleen and Frank’s gift, a changed memory.

Let’s call it October, and a wounded veteran is walking his dog down State Street. Soon he will catch a ride to West Newbury to visit his sisters and try to befriend his great-niece…

Familiar Finds from the Museum Archives

a blog by Sierra Gitlin, Administrative Assistant

At the Museum of Old Newbury, we maintain an extensive archive of records and documents pertaining to local government offices, business, clubs, families and individuals. We have a receipt for payment to Moses Kimball who whitewashed the schoolhouse in 1779, ledger books from ships and shipyards spanning the 18th and 19th centuries, transcripts of speeches delivered at the Fortnightly Club, and the City Improvement Society's 1905 survey of our many noteworthy trees, among other gems. Recently, I was asked to find some promotional materials for the Newburyport Chamber of Commerce. They needed images from Newburyport’s past that they could enlarge and use as displays for their upcoming Annual Meeting on May 18. Of course, every time you open a box (or closet, drawer, or cabinet) at the Museum of Old Newbury, there’s bound to be an interesting surprise inside. But I was stunned and delighted by what I found in the gray archival box labeled “Newburyport Business and Industry.”

Cover image of promotional booklet “Climate for Growth”

It was a strange feeling to find the very familiar looking cover of a promotional booklet called “Climate for Growth,” produced in 1978 by the Newburyport Economic Development Commission under Mayor Richard Sullivan. Although the booklet was published by Newburyport Press the year I was born, the illustrations were immediately recognizable, even though I’d never seen them. “Could it be?” I thought to myself as I looked closer, and carefully flipped to the table of contents. There it was: "Cover and Art Illustrations by Barbara Frake."

They had been drawn by my own mother, nearly 50 years earlier, when she was a recent graduate of Boston University’s Fine Arts program, living in Newburyport to take advantage of cheap rent and a thriving community of artists and musicians. I was stunned that during my regular workday at the Museum, I had just happened upon my mother’s artwork. I took a picture and immediately texted her to see if she remembered working on that book. “Oh yes,” she said, “I had to draw so many teeny little bricks,” and recalled that she had spent several months on it.

International Light, Inc. at 17 Graf Road.

M.V. Electroplating Corp. at 5 Greenleaf St. in the Industrial Park, featured in “Climate for Growth”

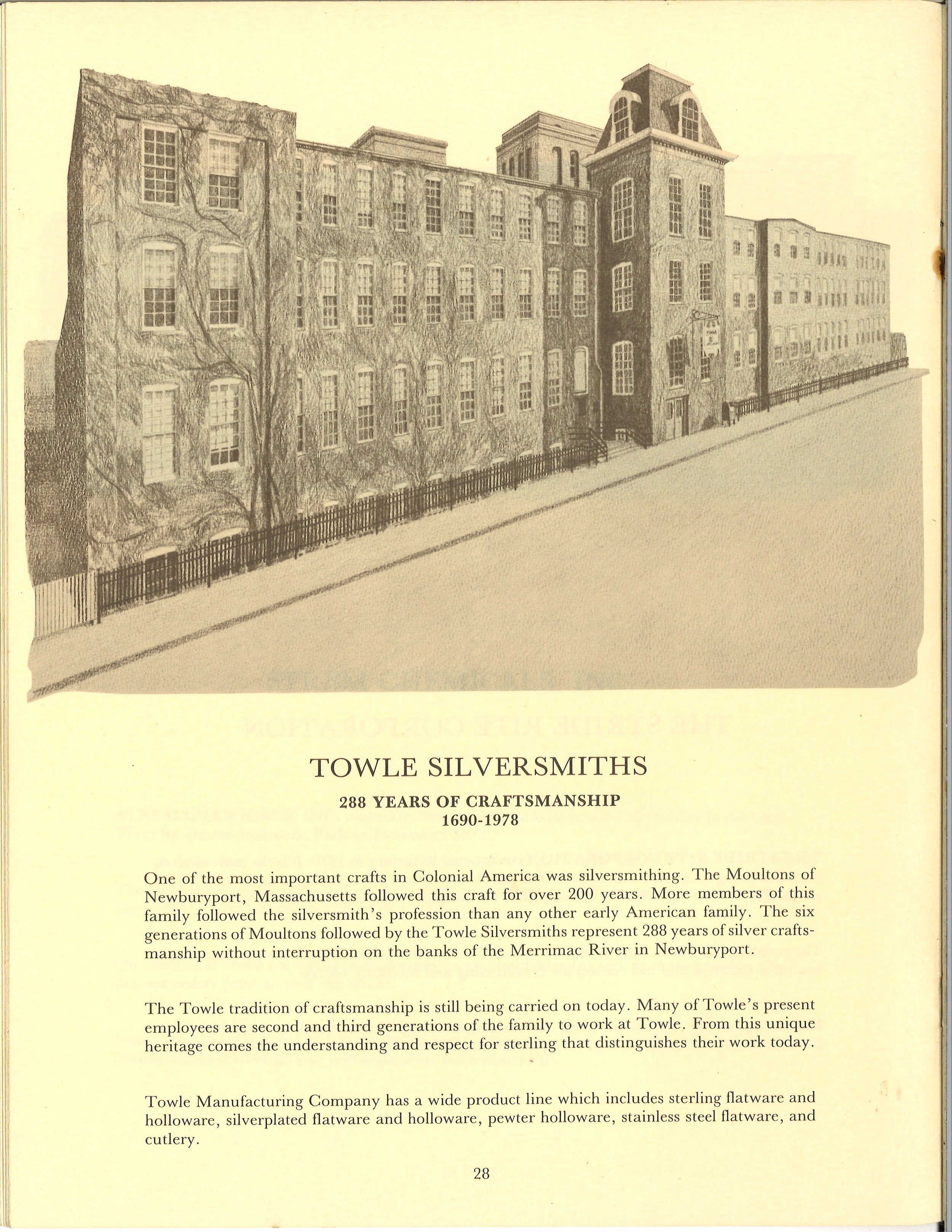

Designed to attract new industry to Newburyport after many years of decline for the port which was no longer among the busiest in the country, the booklet highlighted Newburyport’s economic, demographic, geographic, and historical resources. The then-12 year old Lord Timothy Dexter Industrial Green was featured prominently, as were City Hall, Plum Island Airport, Towle Silversmiths, and local schools and attractions. Some of the drawings’ subjects are unchanged, enduring gems of architecture like the High School atop Mt. Rural. Some will remember that Towle Silver was wrapped from head to toe in ivy back then, but otherwise looks the same. The Industrial Park’s facilities, which by today’s standards appear at best, dated, and at worst, kind of an eyesore, were at the time the height of mid-century modernity, and were deftly captured in painstaking detail by my mother’s pencil, down to the 1970s typefaces of their signs.

Without meaning to suggest, of course, that my mother’s art was anything but an ideal vehicle for showcasing an industrial park, I couldn’t help but wonder why they would hire an illustrator rather than just printing photographs. The answer, of course, which I was slow to realize: photo editing software did not exist yet! So in order to show the buildings looking their best, without power lines, parked cars, or other obstructions, and with tidy plantings, perfect lawns, trees in bloom, etc., an artists’ renderings gave them flexibility they’d otherwise lack to make something ordinary (like a manufacturing facility) look specific and inviting. Similarly, the inside cover of “Climate for Growth” advertises the City’s “Diversified, Tasteful Architecture,” and shows the Dexter Mansion, the Customs House, the Superior Court at Bartlet Mall, plus the Newburyport Lighthouse all grouped together - a photographic impossibility made real through the artist’s imagination.

Barbara Frake's illustration, left, and the original photos she used, right.

Opportunities for illustrators like my mother, whose skill in architectural renderings and graphic design would soon be made obsolete by the advent of software like CAD and Adobe Photoshop, were still plentiful in the 1970s and early 1980s. I also found a 1981 fold-out business directory produced by the Chamber of Commerce. On its cover, a group of tourists young and old look off in the direction of Merrimac Street from Market Square, with three slightly abstract depictions of the buildings across Water Street in the background. Many will remember the slogan “Newburyport. Love at First Sight,” situated above her illustration as the directory’s headline, a simple, monochrome cover created when “cut and paste” involved an Exacto knife and rubber cement. My mother’s style was casual, friendly, detailed, yet restrained, and she drew from photographs she took and had developed at the drive-up Fotomat in Port Plaza or the Kodak store on Pleasant Street.

Left: 1981 Chamber of Commerce Business Directory, Right: Reference photo for “Newburyport. Love at First Sight” brochure.

While digital photo editing and desktop publishing software have certainly made creating promotional materials easier and cheaper, human illustrators imbue advertising with homegrown style and personality. My mother says she really enjoyed working on the Climate for Growth project and many others, mostly for banks and other area businesses. The City of Newburyport was her main focus for several years. She still has shoe boxes full of photographs she took to draw from, a time-capsule of downtown street scenes most people wouldn’t have bothered to capture given the expense of buying and developing film. “When computers made it quick and easy to create precise plans and renderings, I stayed with my fine art background and have been drawing and painting commissions of many subjects, hopefully with a human touch that computers haven’t (yet) mastered,” my mother says.

Pleasant St in the mid-1970s. Photo by Barbara Frake.

While most artists dream of having their work in a museum, having it tucked away and shelved inside an archival box isn’t exactly the fantasy. Still, my mother, who arrived in Newburyport before Urban Renewal, is proud to have helped promote Newburyport and play a small role in its revitalization. While most of her work now involves portraits, horses, landscapes, and an occasional boat, she loves Newburyport as an inspiring treasure-trove of amazing architectural details, and thinks it’s wonderful that ephemera like an events calendar from 1981 are being kept here at the Museum. They are all part of the fabric of the community, and help preserve the stories, people, and places that make us who we are…which is precisely what we at the Museum of Old Newbury are working hard to do.

For the Love of Cars

Guest blog by Kristen Fehlhaber, Assistant Director

This rare, low-number plate with Newburyport roots was recently donated to the Museum of Old Newbury by the Dodge family.

The recent article on Christiana Morgan elicited several interesting responses from readers. Will Rogers of Newburyport wrote to us, remembering his aunt fondly. Thus began a conversation about Christiana and her sisters Elizabeth and Isabella. Will’s mother was Dr. Elizabeth Councilman, a practicing physician in Newburyport from the 1930s-1970s. Her office was in her home at 83 High Street, right across the street from the Museum of Old Newbury. In addition to his mother the physician and his aunt the Jungian analyst, I asked Will about the third sister, thinking she must have led an interesting life as well. This led to a vivid memory of his “Aunt Bay,” an accomplished musician with peculiar car.

Aunt Bay played concert bass and when Will’s high school orchestra performed, she’d drive out from Cambridge to accompany them. The bass poked out of the roof and it was Will’s job to help her bring it in. The car was a tan 1960s Saab 96 with a rag top. It also had an engine that Will remembered as “silly:” a two-stroke that required the owner to mix oil with gas before filling the tank.

“That’s it!” said Will. A 1961 Saab Model 96. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

🚗🚗🚗

Filling the tank might become a thing of the past. The first rumble and roar of classic cars out for Sunday drives started here in New England a few weeks ago, but how much longer will we be hearing those engines? Electric cars are becoming more common and a new EPA proposal announced this week would make gas engines increasingly rare. The first car dealership in Newburyport, opened in April 1905 on Liberty Street, actually featured an electric Pope Waverly car. They were largely marketed to women drivers because of the ease of operations (no gas or steam engine to mess with).

A 1905 electric car from the Pope Motor Car Company catalog. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

🚗🚗🚗

A recent visitor to the Museum shared some stories of his great-grandfather's place in Newburyport’s automobile history. Laurence Paine Dodge (1885-1965) known as “L.P.,” grew up in a mansion at 71 High Street, the youngest child of shoe manufacturer E.P. Dodge.

Built in 1885, this house left the Dodge family in 1926 and was torn down in the late 1930s.

L.P.’s father died on September 30, 1902 at age 54. Just ten days later, on October 10, the 17-year-old became the owner of Newburyport’s first gas-powered car. It was a 1902 Oldsmobile, the first car produced on an assembly line, sporting a curved dashboard and a tiller instead of a steering wheel. We don’t know if this was a gift to comfort the newly fatherless youth; we do know that L.P. remained passionate about cars and driving for the rest of his life.

L.P. in his 1902 Oldsmobile. Top speed was 20 mph. Photo courtesy Laurence P. Dodge II.

n 1902, Newburyport wasn’t prepared for gasoline powered automobiles. There was no filling station, so L.P. fueled his car with five-gallon cannisters that he filtered with chamois cloth, both bought from William Dole at the corner of High and Parker Street in Newbury. L.P. didn’t have to tolerate this inconvenience for long; a gas tank was soon installed at his mother’s house on High Street.

L.P. got his gasoline at Dole’s grocery. The other ads on these pages show that the horse-drawn era was still going strong. 1901-02 Newburyport City Directory.

L.P. got a two-digit plate for this car when license plates became required in 1903. At some point, he lost the rights to the number due to a paperwork issue. However, in 1932, he finagled a way to get plate number 696, which he held onto for the rest of his life.

Based on the number, this plate comes from 1904. Image courtesy porcelainplates.net

L.P.’s granddaughter, Adelaide, remembers that in the 1950s, L.P. lived at 106 High Street and had a pink Nash Rambler convertible, nicknamed “the Shrimp Boat.”

A fine sight on High Street! The Nash Rambler featured bright colors and was compact compared to other American cars at the time. Image courtesy of amcrc.com.

The 696 license plate was even mentioned in L.P.'s obituary! The plate passed down to his daughter Mimi, his granddaughter Anzie, and currently belongs to great-grandson Laurence P. Dodge II of Melrose who said his great-grandfather might not be pleased about his own choice of car.

Laurence P. Dodge II and his 2019 Honda Fit on Fruit Street, sporting the family license plate. Laurence is holding a cup given to L.P. from the Tuesday Night Club. He donated the cup and a license plate to the Museum of Old Newbury.

Laurence says that rules have become stricter and plates can only be passed on to immediate family, meaning that he will be the last Dodge to have plate 696.

🚗🚗🚗

Back to Will Rogers – he reports that he and his brother Henry, both still living in Newburyport, have their parents’ original license plate numbers from when they moved here in the 1930s. Will has 66132 (his father’s), Henry has 66137 (his mother’s). How Will, the younger brother, got the lower number is a story for another time!

If you covet a low-number plate, you don’t need L.P.’s friends in high places – the allotment of these sought-after numbers is controlled in Massachusetts by an annual lottery . With thanks to Laurence P. Dodge II for his generous help with this story. Some details of L.P.’s early driving career come from an interview with him from the Newburyport Daily News, October 2, 1962.

Do You Know What It Means to Miss New Orleans?

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

When I travel, I have always tended to point myself north. I am the happiest in all the world in the Scottish Highlands. Imagine my surprise when, over a decade ago, I fell completely, head-over-heels in love with New Orleans. Of course, it had something to do with falling head-over-heels in love with James Dorau, whose connections to the city and its music go back decades. James had lived in Austin, Texas for many years, and regaled me with tales of driving his Isuzu Pup through the night with his best friend Patrick to see the sunrise over Lake Pontchartrain. They made an annual pilgrimage to Jazz Fest, the 10-day music extravaganza held on the old Fair Grounds Racecourse. When James asked if I would like to go to Jazz Fest with him in 2012, I knew I had made it into the deepest corners of his heart.

Still, I had no idea what I would find in New Orleans, nor did I care. I would have followed James to the moon. What I found there was a place both familiar and foreign, a place rooted in its complicated history and dealing with the legacy of this past as it looks to the future. New Orleans is ancient, steeped in mysticism, suffering, and ecstasy - all the things that I love about old Europe except you can wear a tank top in February and dance all day. There is an openness and a warmth, literally and figuratively, that gets into your bones and loosens up your muscles and those hips just swing all by themselves. New Orleans is hot yoga for the soul.

My happy place, following James and a brass band down the street in 2021. Note: open containers are legal in New Orleans.

That first visit changed me, as the best kinds of travel experiences should. I had been to Charleston and Savannah, so the American South was not foreign to me, but something about New Orleans stuck. Perhaps it’s inherited - my father, another escapee from the frozen North, spent his early college years at Tulane, and has been a trumpet player ever since. When he joined the religious movement that would define my childhood, it was a New Orleans preacher, Sam Fife, who led the group.

Over the past 11 years, with a two-year gap during the pandemic, James and I have returned to New Orleans as often as possible. Sometimes, when airfare suddenly spikes downward, we will go just for the weekend. We eat like kings and dance like loons and laugh and take naps all tipsy and sun-kissed and I wear big earrings and strut everywhere I go.

On the latest trip at the beginning of this month, I had a mission, and a vague sense that I was on the cusp of learning something important about the two most important places in my life – Newbury(port) and New Orleans. The research request for information about Huso and Short mentioned in the Poirier article above had come into the Museum of Old Newbury and I wanted to see the place that connected these two – the streets named after them.

Five Newburyport friends visited the neighborhood where Charles Huso and Samuel Short lived and worked two centuries ago.

We were staying in the Marigny neighborhood, so we walked (strutted) down Royal to Canal Street and hopped on the St. Charles Avenue Streetcar. There were five of us, all Newburyporters, and a reward at the end – a frosty beer and fried pickles at Cooter Brown’s Tavern. I told my companions the story of Huso and Short, or at least the fragmented version of it that I could recall. We took the streetcar to the bend and hopped out. The levee and the Mississippi River were right in front of us, Short and Huso Streets right behind. I took a moment to imagine what this place must have looked and sounded like when Charles Huso arrived in 1824.

There is no substitute for standing in a place. Short and Huso Streets are parallel to each other, the signs marking a relationship between these two men that continued across time and distance. We have so little information about them, but they were clearly connected through commerce, family, upbringing, and experience. The last remaining evidence of this is two streets signs in a city that seems a world away.

A quick visit to Huso Street, at the end of the St. Charles Avenue line.

This was my feeling when I stood looking down Huso Street, noting how it ends at the levee and what a perfect spot it would have been to load and unload ships. The area must have been teeming with seafaring folk, mariners and merchants from all over the world. When I came back home, I did a cursory look through the shipping news in the Newburyport papers. It was astonishing and, given what I know about the misery occasioned by the production of cotton, a bit sickening how often Newburyport ships went in and out of New Orleans. Whoever saved Huso from being kidnapped, it is not a stretch to imagine that it could have been a random, but regular occurrence for him to bump into someone from home. In the Newburyport Herald in 1824, the year Charles Huso took up residence in New Orleans, there were dozens of ships coming and going from New Orleans. The city is mentioned almost daily in surviving copies of the newspaper. We were bound up intimately with the ugly commerce of that beautiful place.

“Arrived, schooner Falcon, Captain Morrison, 20 days from New Orleans, and 16 from the Balize (the outermost point on the mississippi Delta);” Newburyport Herald, April 20, 1824. Digital Archives of the Newburyport Public Library.

I will always be filled with joy when I visit New Orleans, but over the years, I have come to better understand how much suffering is also present in that place. New Orleans is steeped in misery, from slavery to Hurricane Katrina to rampant gun violence and mass incarceration and poverty and racism and the list goes on and on. It is difficult to reconcile this reality – that a place that is so dark can spend its life in constant celebration. I mentioned this to a friend who lives in NOLA. She shrugged. “Life is hard,” she said. “Might as well keep dancing.”

Mourning the Myth

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

I am an accidental liar (I have confessed this already here).

So are you, probably.

But since I am in a position where I am listened to, generally (unless you are my 19-year-old daughter), and presumed to be telling the truth, this is a painful admission. The revelation of my most recent lie particularly rankled because I should have known better.

Here’s the scene. Ghlee Woodworth, a ray of hyper-energized sunshine in our lives, dashes into the museum office, covers a mind-blowing array of topics (ground-penetrating radar, a neighbor’s puppy, owls) in exactly three minutes, and then puts down the bowl of a clay pipe on my desk and explodes back out the door. She jogs on the beach. That must be her secret, I think. I struggle to keep up.

The clay pipe bowl was found by a maintenance worker in Highland Cemetery, likely pushed up and out by the deep freeze. It had legible marking that identified it as a Glasgow pipe from the 19th century, made at the factory of William White. You can see the "W.WH..." in the photo.

Clay pipes were widely smoked, particularly by working people (yes, men and women), before the mass production of cigarettes in the 20th century. Everything I’ve said so far is true, but here comes the lie. “Pipe stem fragments were the cigarettes butts of their time, as people sharing a pipe would snap off the end and toss it before passing it to the next person.”

This 17th century woman has the decency to keep her germ-riddled pipe to herself. “A Woman Seated Smoking a Pipe” by Gabriel Metsu, 1629-1667, Manchester City Galleries.

I have no idea where I heard this, but I announced this “fact” with great confidence before crinkling up my forehead and thinking about it. One of the lasting images I remember from my Little House on the Prairie books is how often everyone shared a water dipper in school, at home, on the train with strangers. Why on earth would people think to snap off the end of a pipe? There was no germ theory of disease. I felt an all-too familiar sinking feeling.

In my feeble effort to verify this “fact”, I stumbled upon a book that is at this very moment insulting and infuriating me. It is called Death by Petticoat: American History Myths Debunked, by Mary Miley Theobald, published under the auspices of Colonial Williamsburg. Let me just say, if I ever run into Mary Miley Theobald in a dark alley, there may be a certain amount of unpleasantness

To set the stage, Ms. Theobald lays blame at the feet of my fellow museum professionals. “It is hard to visit a museum today without encountering these myths.” Surely not at OUR museum!

Not so fast. Here, in order, are myths I believed to be true until I was today years old:

Myth #5: men posed with one hand inside their vest to save money since portrait artists gave a discount if they didn't have to go to the extra work of painting hands.

Makes sense, right? Until you look at all the bajillionaires with their hands in their vests.

Myth #29: Women used arsenic to lighten their complexion.

Close – it was poisonous lead.

Myth #31: Cooks used spices to disguise the flavor of rotting food.

Well, maybe sometimes, but in general, the people who could afford spices could also afford non-rotting food.

Myth #45: The position of a horse’s leg on an equestrian statue tells how the rider died.

I guess not. You have a 1 out of 3 chance of getting this right when viewing a statue, but there is no consistent evidence of this as an intentional practice.

There were plenty more of the 63 myths contained in this volume that I believed at some point in my career, like the one about how beds were shorter because people slept propped up on pillows. I was disabused of this while working for Historic New England, when Abbot Lowell Cummings, former president of (then) SPNEA, handed me a tape measure and told me to measure a bed at the Coffin House. It was about as long as my bed at home, just appeared shorter because of pillowy coverlets and tall posts. Abbot carried a tape measure for just such an occasion. Most beds were made to fit the needs of the family, he said, and would be longer or shorter as needed, but adult beds are almost always over 6’ long.

As I write this, I remember how it felt to have Abbot, a venerated expert in early New England everything, correct my information in front of a group of people. Honestly, it felt – just fine, and I am a sensitive sort. Abbot had a wonderful way of making people feel like he was so excited to share some new bit of information with them – like it was the most natural thing in the world to believe something that is demonstrably untrue until someone shines a bit more light. For Abbot, knowledge was a gift, not a weapon.

Abbot Lowell Cummings in the pulpit of another of my favorite places, Rocky Hill Meeting House. Courtesy of Historic New England.

These myths have a purpose, of course. They make sense and are often based on reasonable observations. They seem to offer a bit of code to unlock the secret messages of the past. And they are good stories, often far more interesting than admitting that something is unknown, or qualifying a statement until it becomes an exercise in pedanticism.

Aside from the shade Ms. Theobald cast on museums, I found myself loving this book. I would be happy to lend you a copy. Most of the “myths” she lists are neither wrong nor right. They are just not applicable to large groups of people. Some people probably did sleep propped up on pillows. Some people died young. Some people were shorter “back then”. Mary Miley Theobald did the hard work of saying “well, sometimes, by some people”, which, in my experience is much harder to do than dispensing generalizations.

But the acknowledgement of the complexity of human experience over time will save the world, I think. Many terrible things have been done by people who believed in eternal, unchangeable “facts” applied to large groups of other people. It is much more difficult to allow for nuance, to acknowledge what an impact race, class, gender, personality, experience, etc. has (and had) on how people live.

Also, in case you were wondering, Venetian blinds were not invented in Venice.

You’re welcome.

Hidden in Plain Sight

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

I did not set out to study women’s history. I did not set out to study history at all. I was an English major, hoping to make it as a writer of…well, that part wasn’t so clear. It wasn’t until that fateful GenEd class at UMass Amherst with Dr. Vincent Ilardi, the Renaissance Optics specialist (his groundbreaking book, Renaissance Vision from Spectacles to Telescopes was surprisingly readable), that I fell deep and hard for history.

Much to Dr. Ilardi’s sorrow, however, his passion for Italian eyewear eluded me. I found myself drawn, as many of us are, to areas of study that connect to our lives. History of the Reformation? Yes, please. I was raised in a Calvinist Protestant world. Crime and Punishment in Victorian England? I read Dickens voraciously. Come on in. I broadened my horizons, took courses with Dr. Yvonne Haddad in Islamic and Middle Eastern history. I went to Imperial Russia, joined the World War, and spent one breathless semester helping Stephen B Oates unpack every prevailing theory about the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Oh, those were heady times.

I was not initially drawn to women's history, despite its obvious connection to my experience. It was regularly offered at UMass in the early 1990’s. There was an entire Women’s Studies department. Though a strong-willed young woman myself, committed to being the captain of my own ship, I had bought into the pernicious idea that history was a set, established set of facts, albeit facts that could be relayed in a dynamic way, and if those facts were relayed by men, to men, and from an overwhelmingly male perspective, that must be just because that was the way it happened. Women were not on battlefields (they were). They were not political leaders, or inventors, or great philosophers (again, they were) …you get the point. The saddest element of this early part of my history education is that I did not even notice that, by and large, the lives of women were not represented in my history books and classes, and if they were, they were in the sidebar, or the exception that proved the rule.

Then, one blessed day, I met Dr. Joyce Avrech Berkman. I think her Intro to Women’s History course met a requirement for the major. Joyce (I can get away with this familiarity today because we are old friends) had long, gray hair in a loose braid over her shoulder. She laughed a lot, easily, but the coursework was challenging, and her standards were high. She was a veteran activist by the time we met and had been one of the chief advocates for the founding of the Women’s Studies program at UMass in 1974.

Dr. Joyce Berkman enjoying a Fowle’s lunch on a visit to Newburyport in 2021.

I think it was her description of British voting-rights activist Emily Wilding Davison throwing herself under the galloping hooves of the King’s horse in 1913, the force-feeding of Quaker suffragist Alice Paul, the desperation and courage of the women on hunger strikes and in picket lines. It was the fact that a married woman could be thrown out of her own house by her husband, denied contact with her children, even deprived of her clothing because nothing she had was hers – because she did not exist as a legal person. It was the vitriol heaped on women who spoke out. Our own Newburyport Daily News had this to say in 1915 about the idea that a woman could exist (and vote) as an individual.

“If she votes differently (from her husband), then the family ceases to come in contact with the state as a unit, and we have the individual and not the family as the unit of society, which is one of the cardinal principles of feminism. And so, I contend that the only consistent suffragist is the socialist and the feminist, because they believe the result of women suffrage will be to destroy the family…”

In the rare air of Amherst, I followed the well-trod path from surprise, to outrage, to sorrow, to awareness. And when I got to awareness, I began to see women everywhere in the historical record, where before they – we – had been invisible to me. They did not only appear as passive victims or warriors against male oppression, either. They often made themselves known in subtle ways, their lives revealed in whispers, easily drowned out by the shouting biographies of powerful men. Sometimes they had been shouting too, but nobody had been writing it down.

When I left academia and the sheltering wing of Joyce Berkman and others like her, I found myself drawn to historic house museums in part because it is so much easier to talk about women in the spaces where most people expect to find them. And still, I remember giving a tour of Coffin House soon after graduate school and realizing afterward that I had told the group that Joshua Coffin was the last resident owner of the house – which was true, but allowed for the erasure of his cousin Lucy, who outlived him by thirty years in the house, but was never its legal owner. In that case, one word changed – last owner became last resident - and a woman’s life was brought back into focus. From that day on, the tours ended not with Joshua’s portrait in the hall, though we spent significant time discussing his remarkable life, but with a tiny, framed picture of Lucy Coffin seated in a straight-back chair in front of what was, in all but name, her house.

I remember once asking a professor why there were no books by or about women in his entire graduate level course on 18th and early 19th century France. SHOW ME THE SOURCES, he shouted. SHOW ME THE SCHOLARSHIP. IT DOESN’T EXIST! We might find it laughable – I hope we would find it laughable today to imagine that there were no women in the French Revolution, no records of their experience, and no women who could write competently about it.

It has come to feel natural for me to meet women in every stage of life, in public and private spaces, even when they were not included in the narratives of the past. Take a well-known male figure in Newburyport history – Tristram Dalton, widely celebrated for his role as Massachusetts’ first Senator (along with Caleb Cushing). His correspondence is voluminous, his portrait easily recognizable to many in this town. His life spanned the early decades of this country, and he experienced many of the same vicissitudes of fate as his peers, ultimately losing his fortune in real estate speculation.

Now let’s try that again. Ruth Hooper Dalton’s life spanned the early decades of this country, and, along with her husband, Tristram Dalton, she experienced many of the same vicissitudes of fate as their peers, ultimately losing their fortune in real estate speculation. Ruth Dalton, of whom no portrait has been found, worked the levers of her own circles of influence and favor, courting the help of Abigail Adams, Martha Washington, and more to ensure that her family did not wind up in abject poverty. Of course, she was also pregnant, nursing, or recently bereaved of a child for most of her adult life. And she managed a busy household that included extended family members, servants, and for a time, enslaved men and women. Her voice is quieter than her husband’s, and the women that worked for her even quieter than hers, but they are there, and they deserve the attention of historians.

Ruth Hooper Dalton spent more time in the Dalton House than did her husband, and certainly more than George Washington or any of the “distinguished men” who visited them both. She is not, however, on the sign.

So now imagine my horror when I recall myself saying to a student who was interested in researching the Black experience in Newburyport, “well, there’s really not much in the way of sources.” Recent research, like Kristen Fehlhaber’s insightful, detailed research into the life of Caroline Cottrell, disputes this idea that this history can’t be done – that there are no sources. I say what Joyce Berkman said to me when frustrated with a research subject that was proving elusive. “Just keep looking”. Those willing to do the hard work of combing through records, reading “against the grain”, often find details of rich and complex lives, hidden in plain sight. Just keep looking.

Neither Underground nor a Railroad

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

This is unfair. Why? I’m going to talk about the subject of an event that is already sold out, with a substantial waitlist, and if I play my cards right, you’ll want to attend even more desperately. Never fear, dear reader. We are concocting a plan to make sure everyone can experience the wonderful Professor Tim Walker and the book that he edited with nine other authors, Sailing to Freedom: Maritime Dimensions of the Underground Railroad.

But since this is my blog, I’m going to tell you about how this book changed MY life and encourage you to read it and think about those moments in your own life when some new information transformed your perception of the world.

Illustrations like this 1893 painting, entitled The Underground Railroad by Charles I. Webber, helped to establish the image of the overland flight to freedom in the American consciousness. Courtesy of Cincinnati Art Museum.

When I was a girl living without a television in the wilderness of northern British Columbia, my reading material consisted of four general subjects: Horses and the Pioneer Girls who loved them, Christian missionaries and the Very Bad Time they generally seemed to be having, post WWI high British fantasy, à la Tolkien and C.S. Lewis, and lastly, a potpourri of history books so old that they escaped the censorious gaze of my parents.

An aside: My mother popped over a few days ago and laughed when I read her the above paragraph. “I poured over the Mennonite book catalog,” she said. We were not Mennonites, but close enough that she felt confident in the appropriateness of their mail-order selections.

Though Mennonite mail-order catalogues no longer arrive at my door, this slim volume made the trip down from Canada and is still on my bookshelf.

I will credit, not so much the Mennonite texts, but the crusty library rejects with my current profession, as among them I found masterpieces on subjects from early New England to Ancient India, and several biographical volumes written by or about the trials endured by enslaved people fleeing to freedom. Of these last works, I recall a well-thumbed volume of Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, and the U.G.R.R embossed on the green cover of William Still’s The Underground Railroad: A Record, both over a century old by the time they made their way to me. Of course, I did not then grasp the full horror of what these books described, but I read these volumes voraciously, imagining the hounds baying in the woods behind me, following the gleam of a hopeful star.

William Still’s The Underground Railroad: A Record was published in 1872 and recorded both overland flight and maritime paths to freedom. This volume is from the Smithsonian.

If you had sat me down just five months ago and asked me to describe the Underground Railroad, I would have told you about enslaved people in the Deep South finding ways to escape overland to freedom in Canada with the help of a network of allies. And if you pressed me to explain why Newbury(port) could have been involved with the Underground Railroad, I may have theorized that people were being brought up via New York state maybe? Connecticut? in wagons through Massachusetts to Maine into Canada? This is not without precedent, as I recall my great-aunt Mary Poore telling me about how Richard Plummer would pick people up in his wagon at the Parker River and hide them amongst sacks of grain, en route to Amesbury and, I assumed, another series of wagon rides to Quebec. I also may have (and this is embarrassing), equated the tunnels that run under Newburyport with some form of escape network. The Underground Railroad is, after all, underground, right?

It's not underground. The tunnels under Newburyport were for drainage, storage, and… I’m sure there were plenty of merchants who were not above avoiding customs agents. But…I am going to plant a deeply unpopular flag here and say that the wealthy merchants who owned the big houses in Newburyport were not designing their houses around an intricate network of tunnels for escapees.

It’s not a railroad either, of course, though some, like Frederick Douglass, hopped a train for part of their journey to freedom.

It's boats. It’s ships and dockworkers and ports and cargo and cash and sailors and the sea. You know - all the things we were and are in Newburyport.

“Light dawns on Marblehead,” as my uncle used to say. “Duh,” as my kids still say. But it took a day with Timothy Walker in New Bedford for this all to sink in.

In late September, the New Bedford Whaling Museum hosted a conference around the topic of the Maritime Underground Railroad. I signed up, still not quite getting it.

My childhood Underground Railroad volume spells it out (though I missed it then). “some (were) guided by the North Star alone, penniless, braving the perils of land and sea…occasionally fugitives came in boxes and chests, and not infrequently some were secreted in steamers and vessels, and in some instances journeyed hundreds of miles in skiffs…”

I was not alone in my limited understanding of how people escaped to freedom. In his presentation at the conference, Dr. Walker noted that the Underground Railroad was primarily conceptualized as a “terrestrial event”, and indeed, the primarily overland routes that enslaved people took to find freedom in the north were the focus of scholarship over the last 120 years. Many of us have seen the famous National Geographic visual indicating the most common routes of the Underground Railroad, and to be fair, it does represent some traffic along the Atlantic coast. But most traffic seems to be coming from Alabama and Mississippi and moving through the Midwest to Canada. But – if a voyage from a Southern port could be made up the Atlantic maritime superhighway in a few days, why are we stuck on this idea of people running through the woods and into wagons, jolting for weeks down country roads and hiding under false floors and under trapdoors?

My friend Kate Clifford Larson said it best in a review of Professor Walker’s book for the journal Civil War Book Review. “Travel by water during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries was the equivalent of quick motor vehicle traffic along today’s superhighways and local road systems. People and commodities were transported most efficiently by small watercraft, larger bay and ocean-going sailing vessels, and steamships rather than overland via terribly limited, unstable, and rutted roads.”

Another perspective shift – most freedom seekers came not from the Deep South, but from within a few miles from a border with a free state. Harriett Tubman was from Maryland, as was Frederick Douglass, whose journey to freedom took less than 24 hours. “It was very, very difficult to escape long distances overland through the hostile territory which was the slaveholding South prior to the Civil War.” According to Dr. Walker, these escapes “almost never happened.”

This thing that I, a well-educated, generally thoughtful human, had assumed was the typical flight to freedom for enslaved people in the 19th century ALMOST NEVER HAPPENED.

There are a variety of reasons for why the narrative of escape has become identified with overland networks – too many, and too interesting to do them justice here. I encourage you to read the book. But let me just say that as the day progressed, the picture I had formed since those days reading musty narratives in Canada was filled in with communities of Black mariners, networks of vessels that could be found with the help of a friendly dockhand, abolitionists who arranged voyages north, and clever captains who waited to report “stowaways” long enough to allow successful escapes.

This notice in Newburyport’s Essex Journal and Merrimack Packet, published the day after the Declaration of Independence, offers a reward for an enslaved man named Robin and specifically warns that “all masters of vessels & others are hereby forbid harboring or carrying off said Negro, they would avoid the penalty of the law.”

This, for me, is the beauty of history as a practice. New sources arise and light shines onto the past in new ways. I am proud to do this work, and grateful to those who continuously open my eyes and change my perspective. I am now scouring early newspapers and other sources anew, looking for clues that could lead to a new understanding of how Newburyport helped or hindered freedom seekers. I encourage you all to join me as we explore history as an ever-evolving, multi-faceted experience, subject to the limitations of language, fettered by the perspectives of its interpreters, and awaiting the discoveries of the future, devastating and delicious in their turn.

(Note: after this blog was published, we were generously offered a larger venue for the upcoming Professor Tim Walker talk - seats still available here at as of 2/18/23)

Aunt Mary in the MACRIS

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

When I was a young teenager living in the Poore House with seven other people (and only one bathroom), I often escaped to another Poore house right down the street. In the 1980’s, there were family homes up and down and just off Garden Street in West Newbury. My grandmother’s brother Ray Poore and his wife Jeanette lived at 48 Garden St, just around the corner from my grandmother’s other brother Howard and his wife Mary. Howard and Mary’s daughter Sue and her husband Gordon lived further down Middle Street, and, of course, my grandmother, Charlotte and her sister Emily Poore lived on Poore’s Lane, where I live today, also off Garden Street. Of the six Poore siblings, four lived within half a mile of each other.

My great-aunt Mary (Anderson) Poore, grandmother Charlotte (Poore) Muzrall, great-grandfather Philip Poore, great-aunt Louise (Poore) Muzrall, great-aunt Emily Poore, and great-uncle Howard Poore in 1955. All but Louise lived on the same street.

I remember Uncle Ray as square-jawed and handsome, not especially friendly to children, but a jokester with his siblings. He owned a large field adjacent to the house where we lived with Aunt Emily and my grandmother, and was a frequent visitor. He stomped into the kitchen smelling of wood smoke and burlap and had my taciturn grandmother laughing about something in short order. I’m not sure he ever spoke directly to me. His wife, my great-aunt Jeanette, was a dragon as well, or so I believed when I was a teenager. Her primary form of communication seemed to be a bit of a growl in my direction, so I steered clear.

Aunt Mary and Uncle Howard with their last dog, Elmer.

But Uncle Howard and Aunt Mary Poore…to me, they were all things wise and wonderful. When I escaped the madding crowd on Poore’s Lane, I often found myself at their house, or, more particularly, in their barn. Aunt Mary had long, snow-white hair, tied back and loose in puffs around her weathered face. She was kind, but in an active, even boisterous sort of way, ready with encouragement or an instruction. Uncle Howard was gentle and quieter. The pair of them offered me sanctuary during some terrible times as I tried to adjust to life in the United States after a childhood spent in the Canadian wilderness, but Aunt Mary and I understood something fundamental about each other. Some girls need a horse, and if one cannot be offered, a barn will do.

Aunt Mary in the 1920's on her horse, Billy.

The barn at 406 Middle Street was an ancient timber-frame beauty. I believe there was still an elderly cow in it when we first arrived from Canada, but my memory on this is fuzzy. Even in the absence of animals, however, it was the perfect comfort to a lost farm girl. The smells were right – the hay still in the loft, the feed sacks stuffed with bailing twine. Dusty harnesses festooned the walls. An old wagon sat in the corner. The hay hook dangled like a funhouse toy from its track along the roofline. I went into the dark and cool of that barn in the summer, sat on an old bale in a whitewashed stall and read books about tough girls who proved everyone wrong, and it made me feel better. And Aunt Mary, trailed by one of a series of yellow and white dogs named Honey, would lure me out with cookies and lemonade and we would shell peas or dead head the flowers in her garden while we talked. She was a devoted nature lover and rehabbed wild birds. I helped her care for crows, cardinals, and a red-tailed hawk. She sent me home with an injured blue jay once– laughing about how much noise we both made.

I wonder what she made of me. One day I told her how much I loved coming to the barn and she invited me to take anything from there that made me happy. I took part of an old harness that reminded me of the draft horses I had left in Canada. It became a sort of talisman, reminding me of another time. As the years passed, it reminded me of Aunt Mary.

The blue jay just before its release in 1987

The barn is gone now. After Aunt Mary died in 1988, followed by Uncle Howard in 1996, the barn became a liability, a barrier to the sale of the property, and it was taken down in 2003. The house was sold. Mary’s daughter Sue and her husband also died, and their house was sold, and most recently, in 2018, tough old Aunt Jeanette died. Her house and barn were sold, razed, and four huge houses popped up in their place, seemingly overnight, their gleaming facades turned boldly to the street. No more hayfield. No more old trees. I’m still not quite over it.

I will admit here that I do not think of Aunt Mary as often as I should. Since the collapse of the Artichoke bridge on Middle Street, closing the section between Garden and Hale Streets, I do not ever drive past her house, once a spur to memory. But last week, as I looked up some information about a West Newbury house in MACRIS, there she was.

Let me back up. MACRIS is short for Massachusetts Cultural Resource Information System. This database links to the Massachusetts Historical Commission database of historic properties – a goldmine for researchers. Better still, the inventory sheets for individual properties, some filled out fifty years ago, are included with the listing. Aunt Mary, clipboard and inventory form in hand, roamed all over West Newbury in the 70’s and early 80’s recording the built environment. I looked up the house and barn at 409 Middle Street. She had filled out the form for her own house in March, 1973, though she filled out the owner as Howard S. Poore. Some of the other bolder women listed houses under the names of the husbands AND wives – even if only the husband was on the deed – a feminist revolution indeed! Though she did not take ownership of her house, Mary Anderson Poore did sign the sheet with her own name, while many of the other women in town signed their names as “Mrs. John Smith”, etc. So, still her own woman. She first takes issue with the name of her street and lists all possibilities. The street is Middle Road or Middle Street, or Plummer Spring Road, or The South Way, or City Lane. Is it open to the public? Rather cheekily, she answers, “Not really.” To know her is to understand that if you asked, she would show you around the place. Scrupulously honest, she admits that her dating of the house as 1750 is based on an old deed and “some conjecture”, and she lists the condition of the house as “fair”, while most of her peers who inventoried their own homes tended to be a good bit more generous in their assessment.

The MACRIS form filled out in 1973 by Aunt Mary

Still, the entire form is filled with her singular personality, and with such fondness for her farm that it makes my heart ache. She notes the “secret room on the 1st floor”, the scuttle near the ridgepole of the roof. She measures the center chimney at 9x12 feet in the cellar, on 2 arches. She lists her “Christian door with 2 small lights in it,” accompanied by a pencil sketch, and the “simple, plain, upright boards” of the exterior. The barn and garage are “old”, while the “henpen, outhouse, cornhouse, baler shed, tool shed and manure shed” are newer. The landscape features are “old farm fields, pastures, orchard, white picket fence behind two large horse chestnut trees.”

There is much I could add here, like how the crocuses and daffodils and irises spilled down the hill by the front door, how the watery light came through the wavy glass of the front room windows, and how she opened every trunk in the attic for me. The MACRIS database is not where I expected a visit from Aunt Mary, but I am so grateful to be reminded of her. This morning there were a dozen blue jays, two cardinals, and a crow outside my window. “Birds can live for a very long time,” she said to me thirty-six years ago, when the blue jay she had trusted to me was recovered and released. “Don’t be surprised when they come back.”

The blue jay just before its release in 1987.

This Old House Visits Our Old House

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

Kevin O’Connor of This Old House at the Museum of Old Newbury

On February 1, 2022, the producer and director of This Old House called the Museum to ask me some questions that had arisen as the team prepared for work and filming at 44 Oakland Street. That phone call led to a Zoom meeting, then another. The house was a mystery, and the team was curious about what we could find out about the people who lived there. The researchers at the Museum got to work sleuthing out the story behind the house. What we uncovered was a rich and unexpected history of a little-documented life.

Meet Hannah Twomey. I wish I could show you a picture. What I can show you is the first time her name appears on a Newburyport census, in 1880. She is 20 years old, a servant in the household of Caroline Johnson on Federal Street. From the 1900 census we learn that she arrived from Ireland as a 15-year-old.

Hannah Twomey (also spelled Toomey in several sources) spent most of her life living in the homes of her employers, but on August 7, 1889, just shy of her thirtieth birthday, she bought a piece of land from John Casey on Oakland Street. Sources are somewhat hazy about when the house was built, but we know that a house is there by 1892, with directories listing Byron S. Hatch, silversmith, as a tenant at 44 Oakland Street from 1892-1898, joined by his brother George H. Hatch, clerk, in 1898.

Over the next four decades, the house is home to a variety of family configurations and professions, most connected to the industries that had steadily moved west from downtown and were now stretched along the Merrimack River along the bottom of Oakland Street. From 1902-1925, Fred H. Stover, iron moulder, was listed, joined by Ernest Stover, shoe-cutter from 1904-1925 and Bertha T. Stover, stenographer, in 1912. Another moulder, Thomas Bruce, was in residence from 1927-1935, and from 1937-1939, C. Henry Kelleher, chauffer, lived there with his family. We can assume that other tenants came and went, and that the house was sometimes divided between multiple families, as the designation “rear” is sometimes used.

The 1912 directory lists Hannah Twomey at 20 Fruit Street while across town...

four members of the Stover family are living at Hannah's house at 44 Oakland St.

What we know, is that Hannah Twomey did NOT live at 44 Oakland Street during her lifetime. As we followed her through the directories and other records, we found her living and working as a servant at prestigious addresses on Federal, High, and Fruit Streets, as a cook at the “Old Ladies Home”. When not living in service, she helped her sister Nora’s family with their grocery business, and lived with them on Carter Street.

Hannah Twomey was a challenge to research. Her name was common in both Ireland and Newburyport and she lived where she worked rather than in the house she owned. We looked for a record of her death, but came up empty. Intrepid researcher, assistant director Kristen Fehlhaber, was on the case, and after an exhaustive search, she found the estate of Johanna Twomey being settled in 1937. Board member Jane Wild helped to understand the probate records, which split her estate between two siblings in Ireland and two in Newburyport. Searching Newburyport deaths year by year, we eventually found a Johanna Twomey dying in 1934; a quick walk to Newburyport City Hall and$25 gave us her death certificate. She died on April 5, 1934 at her sister's house after a ten day illness.

Hannah Twomey’s July, 1937 probate notice offered the biggest clue, listing her as both Hannah and Johanna

the Probate led to finding her 1934 death certificate, obtained from city hall

In 1939, five years after her death, 44 Oakland Street was sold to Lawrence & Mary Twomey by Hannah Twomey’s siblings. While it is natural to assume that these families were related, no evidence has been found, and the house was sold at roughly market rate. Lawrence “Larry” Twomey worked at Leary’s Package Store and had owned the Park Lunch restaurant on the corner of Kent and Merrimac Street since 1933 or 1934.

This Old House came to the museum to film in mid-March. I was NOT a natural. I could not remember what I had just said when asked to do a take a second time. My neck and my ears went bright red, and I repeatedly referred to host Kevin O'Connor as Kevin Connell. Despite all this, the entire experience was wonderful. Apparently I was not the first nervous civilian to flub her lines on the show, and everyone was extremely patient, including the homeowner, Melissa, who was a seasoned cast member by this point.

This Old House Cameraman Steve D'Onofrio and I ham it up at the wrap party with my husband James Dorau.

It helped a great deal that the head cameraman and I have mutual friends and that I worked with one of the producers years ago at Historic New England. And, of course, Kim Turner, Newburyport’s Manager of Special Projects at City Hall, and a longtime friend, was on two seasons of the show as a landscape designer. It also helps that the dining room of the Cushing House, whatever nonsense is occurring within it, is stunning from every angle.

This Old House host Kevin O’Conner holds the elusive death certificate of Hannah Twomey while I chat with homeowner Melissa during filming.

This Old House came back a month later to film again, and it was a joyous reunion. I think I finally got the hang of it, though much of that visit wound up on the cutting room floor.

Host Kevin, producer and director Adam, and yours truly on the boardwalk on a cold, damp day in April.

In addition to the national visibility that our appearance on the show affords the Museum of Old Newbury, it was personally deeply gratifying for me. My dad and I watched This Old House together for years, back in the days when you had to block off the time and rush to the tv to see Norm and Bob. Upon hearing this at the wrap party in August, Charlie Silva of Silva Brothers' Construction ran out to his car and gave me a shirt for my dad, which he wears, along with his Silva Bros. hat, while he reads This Old House magazine. And Kevin, who sat through multiple retakes and had to shake my clammy hand over and over again, turned out to be just as funny, happy, and kind as he seems on television.

My dad is sporting his new favorite shirt, courtesy of Charlie Silva.

The most gratifying part of the experience for me, however, was talking about (Jo)Hannah Twomey. In a city long associated with Federal Houses, old English families, and the sea, this plucky woman worked hard to make a life for herself here, invested in real estate at just the right time, and helped to support her family in life and in death, even as she disappeared down the back stairs and into the kitchens of the grand houses of Newburyport’s elite. I will never forget her, and it was my great honor to bring her alive, in a small way, to a national audience. I am eternally grateful to This Old House for the opportunity to do her this service.

Last night, the Port Tavern was filled with fans of Newburyport history for a live viewing of This Old House.

Guest Blog - You Can Go Home Again

by Sierra Gitlin, Administrative Assistant

Spending your days sifting through old photographs and extensive genealogies, as we do at the Museum of Old Newbury, can make you question your bona fides as a Newburyporter. This small city, like many, I suspect, has a strong sense of the importance of its storied families. Familiar surnames repeat themselves on street signs, landmarks, memorials, buildings, and tombstones, and many descendants of the first European settlers who landed on the Parker River in 1635 still live here. How does someone like me then, who measures my time here in just a couple of interrupted decades, not in unbroken centuries or generations, come to call Newburyport home?

Market Square circa 1979

My earliest memories are of my own feet slapping along the bricks of Market Square, chasing pigeons on Inn Street to the sandy tot lot, breakfast at Fowle’s, preschool in the YMCA basement, and what seemed like hours sitting in Ferlita’s while my dad played (dominated, to hear him tell it) the Missile Command arcade game. My parents met at the Grog in 1974. Mom was a waitress and dad was in the band that was playing that night.

The Grog - still in business today in 2023!

She had moved here shortly after graduating with a fine arts degree from Boston University, because Newburyport was, at that time, an affordable place to live with a thriving arts scene. Her apartment on Dalton St. was $90 a month. My dad quickly fell in love, with my mother and with this seaside town, and relocated from Vermont where he had been spending his early 20s skiing and playing in a rock and roll band. When I was born in 1978, we lived at 48 Milk Street.

The South End was a different place then - our house was broken into often, my mom once had to buy her stolen wedding ring back from a pawn shop downtown. Eventually we moved just over the border to Newton NH, where I did most of my schooling, my parents attracted to the quiet, privacy, and breathing-room of the country. But Newton had no grocery store, no bank, barely a gas station at that time, so we would come to Newburyport several times a week, and always on Saturday mornings, to shop, do errands, see friends, and have breakfast at Fowle’s. As soon as I got my driver’s license, I’d come hang out in Newburyport, back on Inn Street. I was too old and too cool to chase pigeons, never too old for a jaunt to Fowle’s for hot chocolate, and just old enough to be making calls from the wooden phone booth in the front corner. But I was always a bit of an outsider, since I didn’t live here anymore, or go to school here. I was from two places - these brick sidewalks, and the woods of NH.

Looking up Inn Street from the fountain. Note the balloon seller.

Despite living elsewhere from the ages of 6 to 24, my early years in Newburyport, and my family’s weekly, almost ritualistic, return throughout my childhood and teen years made it feel like my true home. Once I grew up and got married, it was the only place I could imagine living and raising kids. Luckily my husband was amenable, and we were able to buy a house back in the South End, just steps from where I started my life. My kids were born at Anna Jaques Hospital, and I pushed them in strollers to the new playground on Inn St, where THEY took their turn chasing the pigeons. We had many breakfasts at Fowle’s when they were very young, just before it closed and changed, and changed again. I was able to walk them downtown to preschool at Newburyport Montessori, run by the same remarkable women who ran Spring Street School, where my mom had walked my brother and me 30 years earlier.

A last photo of Fowle's before it closed in 2012.

I've now lived here as an adult longer than I lived in New Hampshire or anyplace else, and though my genealogy has no ties to any early settlers at all - my ancestors immigrated from Ukraine, Europe, and the UK around the turn of the 20th century - Newburyport is my home, and my children’s home. My life’s seemingly wandering path has actually led me in a circle. I can see my first house on Milk Street from my bedroom window here on Orange Street, where I’ve been lucky enough to call the purple, turreted Queen Anne Victorian “Moody House” my home for the past 16 years. I am rooted here not by birth, but by choice, by luck, sometimes I think even by destiny, given how close to my starting place I now live. Once you've spent time in Newburyport, it’s impossible not to feel a deep connection to this spectacular bit of coastline and riverbank and marsh and woods. Working at the Museum of Old Newbury, learning more than I knew there was to know about Newburyport and the families and individuals who built it, that connection has only grown. It sounds like a cliché, but home really is where the heart is, and whether your family has been here for three years, three decades, or three centuries, it’s easy to be madly in love with the beauty and history of this remarkable city.

Comfort and Joy

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

It’s three days before Christmas and I’m feeling blue. Scratch that. It’s three days before Christmas and I’m grieving. If you are feeling unequivocally merry and bright, you might want to give this post a miss. If, on the other hand, you are feeling out of step with the glitter and glitz of the holiday season, like so many of us right now, you’re in good company.

On Monday, we lost Cathy Strauss. There should be a descriptor after her name. I should say, Cathy Strauss, past co-president of the Museum of Old Newbury, or Cathy Strauss, friend to me and many others, or Cathy Strauss, beloved sister, mother, aunt. Cathy Strauss, master of the cheese plate, the devilled egg, the pigs in blankets, the arched eyebrow, the hearty laugh, the witty quip. Cathy sallied forth into the office here with a shout of “hello, lovely ducklings!”, or “hello, beautiful people!”, exclamations of delight at our very existence. She set the tone for what this museum is at its best – part garden party and part disco inferno with fabulous art and excellent snacks. Cathy was very much at home at the Museum of Old Newbury. She had been a docent, a board member, and most recently, co-president. Her roots in Old Newbury go back centuries, a descendant of Hales and Littles and Tenneys and Poores. Like me, she grew up “away”, but made a life for herself here, embracing the history and memory of her family, and for both of us, this connection had led us to the Museum of Old Newbury, where our circles grew deeper and wider.

Cathy Strauss speaking at the 2021 Annual Meeting in the Perkins Mint at the Museum of Old Newbury.

In the first moments of awakening this morning, when things were both softer and clearer for me, I brought Cathy’s face into my mind’s eye. She came into focus with her sisters, soon joined by my friend who just lost her father, another whose mother is disappearing into Alzheimer’s, dear friends who have lost soul companions of all kinds. Then, the letting go, the hard morning light, the pressing obligations. I went outside with a handful of carrots and spent some quiet moments with the animals.

Death, in all its forms, is a universal human experience. In a way, it is the most present reality of our work at the Museum of Old Newbury. Every day, we are thinking about people who have died, organizing their possessions, dusting their relics, looking into their faces in paintings, statues, photographs. We are talking to their children and grandchildren about who they were and what they left behind. The museum itself is a place where people make friends and meet neighbors, and it follows naturally that the loss of members of our community is deeply felt here as well. We are all swept along together in a deep river of friendship, love, and loss.

At the intersection of Low Street and Rte. 1, I pulled up to a red light and found myself unable to control the tears that had been building all morning. I do not cry often, but when I do, it’s not pretty. A quick glance to my right confirmed that there was a woman in the car next to me, looking away. I sniffled. She looked over. She was crying too. The two of us, complete strangers, both wearing holiday sweaters and jaunty scarves, had a moment together weeping uncontrollably, and then, recognizing the ridiculousness of it all, laughing together at a stop light.

Cathy and her sister Beth share a secret at the Museum's 2022 Annual Meeting. Photo courtesy Bob Watts.

I took a detour after that. I drove down High Street into Newbury, pulled over in front of Coffin House, and crossed the street into the First Parish Burying Ground. I had a mission – I needed a picture of a stone for an upcoming story. But it was more than that. Standing among the people who have walked this bit of the earth over time comforts me. It reminds me that in our awareness of our mortality lies our essential humanness. Tonight, Ghlee Woodworth and I will lead a merry band of flashlight-wielding neighbors and friends through Oak Hill Cemetery on the longest night of the year. It will be dark and cold, but we will be together, travelling through time, lighting the path for each other, and celebrating our neighbors, living and dead.

I wish you comfort this holiday season, if you need it. If you have some to spare, share it with your neighbors. I will always smile when I think of Cathy, with her throaty chuckle and her perfect union of sass and class. We were lucky to be here with her.

For more information, see the obituary in the Newburyport Daily News.

The Center of the Universe

by Bethany Groff Dorau, Executive Director

Picture the scene - yours truly, perched on the edge of a comfortable leather sofa in a recreated pub below decks on the ship Queen Victoria, cruising through the Bay of Biscay between France and Spain. The occasion is the nightly pub quiz, a British tradition that, like other British traditions, forms the social calendar of our recent voyage. We are part of a team of 6, trying to identify songs by Fats Domino and Whitney Houston. I'm shouting over the throbbing strains of "I Wanna Dance with Somebody", recapping our plans for port excursions in Spain. One of the party declares that I must see the Alhambra. "The bus is full," I shout. "We’re going to Cordova."

The Spanish city of Cordova has been an important craft, trade, and religious center since the 2nd century BC. Courtesy image.

And then it happens. My quiz buddy says something about cordovan leather, and we're off to the races. “You know what's funny” I say, “I was always seeing these early Newbury records that refer to cordwainers. Did you know a cordwainer is someone who works in new leather? It's a derivation of an old French word meaning someone who works in cordovan leather, originally the finest leather from Cordova! The term cordwainer was used to distinguish people who made shoes from new leather from cobblers, who repaired shoes, in the medieval guild system in England. Did you know that cordovan leather is made from the connective tissue under the skin of a horse’s rump? Cordovan leather was so expensive that the term became synonymous with the finest quality leather, and so it became sort of a high-end brand, and everyone started using it on all kinds of leather goods.” My friend’s eyes were glazing over.

“Anyway, you probably know all that already,” I said, making the natural assumption that British people are all fonts of historical knowledge. “I didn’t, actually” he shouted politely, “but I do know that this song is 'Hip to be Square' by Huey Lewis!”

These tiles mark the shop of a leather merchant in Cordova in eight different languages.

I had so much more to say about arcane adventures in leather. I wanted to tell someone about my recent discovery in several account books that dog carcasses, DOGS, were sold en masse to the Coffin tannery on High Road in Newbury, and that far from being some sort of aberration, dog skin was widely harvested, considered the best for making strong but supple gloves, particularly for women. William Shakespeare himself mentions the article in his jointly written play, Two Noble Kinsmen, as a character notes that “the next gloves that I give her shall be dog skin.” Our own Louisa May Alcott mentions the offending article in Little Women. "Uncle rushed out and bought a pair of dogskin gloves, some ugly, thick shoes, and an umbrella, and got shaved _à la_ mutton chop, the first thing."